Coins and History of the Roman Wars with Persia in the Second and Third Centuries

Coins that illustrate wars between Rome and Persia:

Roman imperial, Roman provincial, and Persian coins

|

|

Septimius Severus, 193-211

An imperial denarius. 18 mm. 3.40 grams. Struck 198.

VICT PARTHICAE, Victory advancing left holding wreath and trophy, captive below.

RIC 514 from an eastern mint (possibly Laodicea near Antioch)

The obverse legend ends "PART MAX" for "Parthicus Maximus"

a title he was awarded for his Parthian victories.

|

Valerian, 253-260

An imperial antoninianus. Radiate bust. 21 mm. 2.39 grams.

VICT PART, Victory standing left holding shield and palm. captive at feet

RIC 262 from the mint of Viminacium [according to Cunetio].

In 256 Valerian recaptured Syria from Shapur I (who had taken northern Mesopotamia, Antioch, and Tarsos) and minted victory types. Then, in 260, while attempting to recapture northern Mesopotamia, he led the famous catastrophic campaign in which he lost an army of 70,000 men and was captured alive by Shapur I (directly below). |

|

|

Philip I, 244-249.

A Roman "provincial" coin of the Mesopotamian city Nisibis

("NЄCIBI" on the reverse from 12:30 to 2:30).

26 mm. 9.98 grams.

AVTOK K M IOVΛI ΦIΛIΠΠOC CЄB

(Autokrater Caesar Marcus Julius Philippus Sebastos)

Rev: IOY CЄΠ KOΛΩ NЄCIBI MHT,

(Julia Septimia Colonia Nisibis Metropolis)

[This "Julia" is a family name for Philip. The "Septimia" is because Septimus Severus gave it the status of a colony]

Tetrastyle temple containing statue of city goddess seated facing; above her head, ram (Aries) leaping right; below, river god Mygdonius swimming right.

Sear Greek Imperial Coins 3970. BMC Mesopotamia Nesibi [sic, that is how it is spelled on coins, although it is spelled "Nisibis" in literature] 17 |

Shapur I, Sasanian (Persian) King, 241-272 (possibly 240-270)

A drachm. 27 mm. 4.46 grams. Thin.

King right with his distinctive headdress. Fire altar with two attendants.

Sellwood, Shapur I, 14.

Shapur captured Hatra and Nisibis and invaded Syria c. 241, capturing Carrhae and Antioch. Gordian III defeated him in 243 at Rhesaena and regained Antioch, Carrhae, and Nisibis. However, in his final battle Gordian III died and Philip I retreated, but Rome retained those cities. Then, c. 253-256, Shapur reclaimed northern Mesopotamia and invaded Syria and sacked Dura-Europus and Antioch. Valerian counterattacked and regained Syria, for which he issued victory types (the coins directly above and below). However, while attempting to regain northern Mesopotamia, Valerian lost a huge army and was captured. While preoccupied in the east Shapur I lost some of Mesopotamia to the short-lived Kingdom of Palmyra. Aurelian (270-275) restored the Orient to the central empire by conquering Palmyra in 273. |

This page discusses ancient coins that illustrate the wars between Rome and Persia. The wars were often fought in northern Mesopotamia which was closer to the heart of the Persian empire than to Rome. Nevertheless, northern Mesopotamia was usually under Roman control between AD 164 (when the region was conquered under Lucius Verus) and AD 363 (when it was lost after Julian the Apostate was killed). "Mesopotamia" means "[land] between the waters [i.e. rivers]" that is, between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

This page discusses ancient coins that illustrate the wars between Rome and Persia. The wars were often fought in northern Mesopotamia which was closer to the heart of the Persian empire than to Rome. Nevertheless, northern Mesopotamia was usually under Roman control between AD 164 (when the region was conquered under Lucius Verus) and AD 363 (when it was lost after Julian the Apostate was killed). "Mesopotamia" means "[land] between the waters [i.e. rivers]" that is, between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

Coins. The coins include

1) Roman imperial coins that mention victories over Parthia or Persia. This is the largest category.

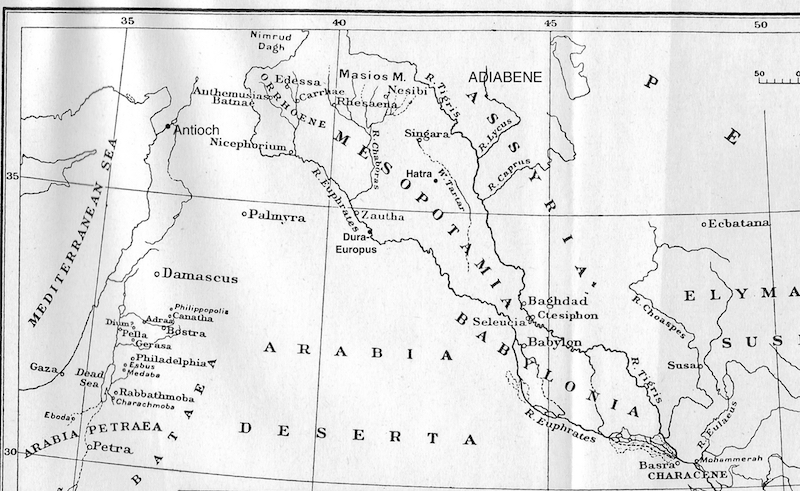

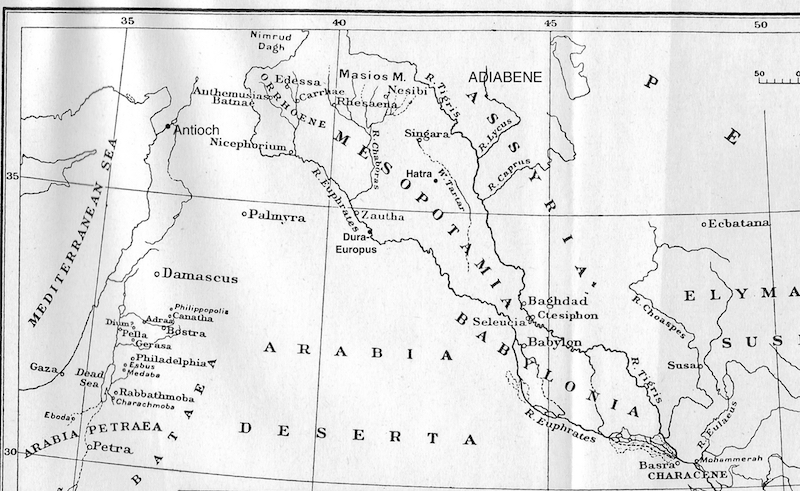

2) Roman provincial coins that document Roman control of Mesopotamian cities (Edessa, Carrhae, Rhesaena, Nisibis, and Singara, all in northern Mesopotamia). These cities were usually Roman, but sometimes taken by the Persians and sometimes besieged by the Persians but successfully defended by the Romans. This map is from A Catalogue of Greek Coins in the British Museum. (Click on the map to enlarge it.)

3) Parthian and Sasanian coins. "Persia" is a catchall term used for the geographic region of Parthia before AD 224 and the Sasanian Empire after AD 224. Unfortunately, Persian coins do not make reference to events the way that Roman imperial coins often do, but they do have portraits of the kings who were fighting the Romans.

What's new? 2025, August 20: Macrinus tetradrachm from Carrhae.

2025, July 27: A map emphasizing mountains.

2025, March 29: Images linked to larger images. Click the image to see a larger version of the same image.

2024, Dec. 15: Gordian III at Carrhae.

2024, Sept. 29: An extremely rare Caracalla VICT PARTHICA denarius.

2024, August 7: Gordian III at Singara which mentions Legion III.

2024, April 28: Caracalla at Carrhae.

Table of Contents of this Page: Coins and their related history in chronological order.

The Roman provincial coinage of the Mesopotamian cities, by city.

A timeline of events with links to related coins.

A few caveats about history.

Other pages: A second page of photos.

A page of references.

A page which lists the Roman emperors and the Persian rulers who opposed them.

Roman Emperors and their Coins. Trajan (98-117), Lucius Verus (161-169), Marcus Aurelius (161-180), Septimius Severus (193-211), Caracalla (196-217), Marcinus (217-218), Severus Alexander (222-235), Gordian III (238-244), Philip I (244-249), Trajan Decius (249-251), Valerian (253-260), Vabalathus of Palmyra (271-272), Aurelian (270-275), and Carus (282-283).

Who was the Persian ruler at the time? Here is a page with a table which gives the Persian ruler at the time of each of these Roman emperors.

Wars before Trajan (A.D. 98-117):

• 53 B.C. - A.D. 115 – Roman armies suffered famous disastrous losses in Persia under Crassus at Carrhae in 53 B.C. and under Marc Antony in 36 B.C. In 20 B.C. Augustus recovered the lost standards by diplomacy, not by war. In A.D. 58 under Nero the Roman army replaced the pro-Parthian ruler of Armenia while the main Parthian forces were fighting elsewhere, but in 62 the Parthians struck back and reversed all the gains. Then a compromise allowed both sides to keep a hand in Armenia and served to keep the peace for 50 years until the time of Trajan.

• A.D. 115ff. From Trajan onward all the coin-related history is stated and illustrated in chronological order next. The history is also consolidated into a single timeline far below.

Key: Links from names are to coins illustrated on this page.

Links labeled "(coin)" are to additional coins illustrated on a second page.

Coins and the stories they tell.

• A.D. 115-118 – Trajan (98-117) installed a pro-Roman King in Armenia and invaded Mesopotamia. Its capitol Ctesiphon was sacked in 117. When Trajan invaded Parthia he brought along a Parthian prince, Parthamaspates, who had been in exile in Rome to install as puppet ruler. It proved impossible to occupy Persia for long, so his successor Hadrian withdrew from most of Mesopotamia. No Roman provincial coins were issued in Mesopotamia until Marcus Aurelius. (Here is a short page on related coins of Trajan.)

Trajan, 98-117.

Trajan, 98-117.

Large sestertius. 34 mm. 29.56 grams.

Bust of Trajan right

Trajan standing right holding spear and parazonium (sheath with short Roman sword)

with Armenia personified (with a distinctive cap) seated at his knee between the river gods of the Euphrates and Tigris reclining (enlarged below).

The reverse reads: ARMENIA [5:30 to 7:00] ET MESOPOTAMIA [7:30-10:30] IN POTESTATEM P R REDACTAE SC

Armenia and Mesopotamia into the power of the people of Rome taken back [in the form of a province], the Senate consulted

RIC Trajan 642. Sear II 3181. Struck 116 AD at Rome.

Armenia personified between the river gods of the Euphrates and Tigris reclining. Do you see the water pouring from the overturned jug on which the god on the left rests his right forearm?

[Another page on my site has more about this type.]

Armenia personified between the river gods of the Euphrates and Tigris reclining. Do you see the water pouring from the overturned jug on which the god on the left rests his right forearm?

[Another page on my site has more about this type.]

When Trajan invaded Parthia he brought along a Parthian prince to install as puppet ruler. Parthamaspates had been an exile in Rome. The next coin has been attributed to Parthamaspates in the main reference works, but see comments below.

Parthamaspates, 116.

Parthamaspates, 116.

Drachm. 24-18 mm. 3.69 grams.

The short beard acknowledges his youth.

A crude seated Parthian archer holding out a bow over a stool with Greek lettering around.

After the capture of Ctesiphon and Babylon, revolts in captured cities and in Armenia, along with the regrouping of Parthian cavalry which had not been destroyed, forced Trajan to withdraw. The Parthian Osrow (Osroes) rapidly dethroned Parthamaspates who fled to the Romans and was granted the small buffer Kingdom of Osroene (Osrhoene) centered around Edessa.

Sellwood 81.1. Shore 423.

On CoinTalk after I first announced this site, the member Parthicus wrote, "Assar's argument against Parthamaspates as the issuer of S. 81 coins is as follows: Parthamaspates had influence only in and around Ctesiphon (which was not a mint city for the Parthians), where he was protected by the Romans. However, the S. 81 coins were probably struck at Ekbatana, in Media on the Iranian plateau, far from Parthamaspates' zone of control and a region controlled by enemies of the Romans and their puppet." So, maybe this is not Parthamaspates after all. He closed his comment with "The situation is messy and far from certain; in other words, perfectly normal for Parthian numismatics."

Trajan was unable to capture Hatra. After Hadrian withdrew we know Adiabene and Dura-Europus remained in Roman hands, but what else remained Roman is uncertain. Some think the border became the upper Euphrates.

• A.D. 117 – Hatra withstood a siege by Trajan. It was a large Arab caravan fortress city with more than four miles of walls and 160 defensive towers.

Kingdom of Hatra, 2nd - 3rd C,. This type likely 117-138.

Kingdom of Hatra, 2nd - 3rd C,. This type likely 117-138.

25 mm. 12.12 grams.

Draped bust of beardless radiate sun god, Shamash, right

Aramaic legend "Shamash"

The reverse has "SC" like coins of Antioch, but upside down in wreath under eagle with spread wings (That and the leaves of the wreath which tell us which orientation is up). I have not seen a credible explanation for why the coins all have "SC" upside down.

This coin type is #7 in Slocum, who notes an overstrike on a coin of 115. Hatra withstood Trajan's siege in 117. Slocum suggests Hadrian may have subsidized Hatra as a buffer state.

Antoninus Pius (138-161) has one very rare sestertius (with legend "PARTHIA") with Parthia standing and offering crown gold for his accession.

• A.D. 161-166 – Lucius Verus (161-169) led a war against Parthia under king Vologases IV (c. 147-191, sometimes spelled "Valaksh"). In 162 Vologases IV had installed a pro-Parthian ruler in Armenia and conquered the fortress-city of Edessa, seat of the Kingdon of Osrhoene. In response, Verus first successfully invaded Armenia and in 163 installed his own pro-Roman ruler to cover his northern flank, and then invaded all of Mesopotamia and sacked Seleucia and Ctesiphon. (Actually, his generals did it while Verus enjoyed the delights of Antioch). Dura-Europos (overlooking the Euphrates from the west) was captured and occupied by the Romans, ending Parthian control. Dura-Europus was recaptured in 241 by Shapur I (241-272). Dura-Europos did not issue coins, but archaeology has found many written records there that illuminate our understanding of the Roman/Persian borderlands. Whether any of the rest of northern Mesopotamia remained occupied by the Roman army is uncertain.

Lucius Verus, 161-169

Lucius Verus, 161-169

Denarius. 18 mm. 3.30 grams.

L VERVS AVG ARMENIACVS

This clearly states his conquest of Armenia which was a necesssary precursor to invading Parthia.

TRP IIII IMP II COS II

ARMEN in exergue.

Personified Armenia seated mourning before pile of arms and standard

"TRP IIII" dates this coin to Dec. 163 - Dec. 164

RIC 509, Sear II 5347v (IMP IIII, not III).

There are coins like this for Marcus Aurelius and coins like this without ARMEN in exergue (coin).

Lucius Verus, 161-169.

Lucius Verus, 161-169.

Sestertius. 34-31 mm. 28.87 grams.

L AVREL VERVS AVG ARMENIACVS

Conquerer of Armenia

REX ARMEM / DAT (weak, in exergue)

"King given to Armenia"

Lucius Verus on dias crowning King Sohaemus of Armenia.

TRP IIII IMP II COS II

RIC 1370. Sear II 5374 variety (Sear's type has REX ARMEN DAT around instead of in exergue).

Rome didn't exactly incoporate Armenia into the Roman Empire, rather it appointed a pro-Roman client King.

Lucius Verus, 161-169.

Lucius Verus, 161-169.

Denarius. 19 mm. 3.39 grams.

Victory holds palm and a shield inscribed VIC/PAR on a palm-tree column

TRP VI IMP IIII COS II

"TRP VI" dates this coin to 166.

The obverse legend

L VERVS AVG ARM PARTH MAX

The obverse legend cites, with "ARM", his Victory against Armenia and with "PARTH MAX" his victories against Parthia as the greatest.

RIC 566. Sear II 5359.

This type was shared with Marcus Aurelius (next).

• A.D. 165 – A severe plague broke out among the army at Seleucia which forced Roman withdrawal (One source says 15% of the soldiers died). The soldiers brought the plague back to the Roman empire where it caused very many deaths. Parthia suffered similarly from the plague. Upon the return of Lucius Verus return to Rome he shared his triumph with his co-emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Marcus Aurelius, 161-180.

Marcus Aurelius, 161-180.

Denarius. 18 mm.

M ANTONINVS AVG ARM PARTH MAX

Head right, laureate

TRP XX IMP IIII COS III

Victory right holding plam and shield in scribed VIC/PAR on palm-tree column.

RIC 163. Sear II 4933.

Struck summer-December 166

Other types of Lucius Verus were also shared with Marcus Aurelius (coin).

Vologases IV, Parthian king (c. 147-191) when Lucius Versus conquered Parthian territory.

Vologases IV, c. 149-191

Vologases IV, c. 149-191

Drachm. 19 mm. 2.11 grams (light)

Crude portrait left

Archer seated right holding out upside down bow over stool

Very crude Greek lettering, mostly dots around the seated archer with his bow.

I showed this coin in person to David Sellwood and he said it is not an imitation, rather a crude original. Apparently, many of the coins of Vologases IV are poorly produced.

Sellwood 84. Shore 435, but cruder.

• A.D. c. 193 – Vologases V (c. 191-208) took advantage of the civil war between Pescennius Niger and Septimius Severus to take Adiabene and Armenia. Then internal revolts against Parthian rule left Vologases V unable to concentrate on the Roman response.

• A.D. 195-199 – Septimius Severus campaigned against Parthia under king Vologases V. Septimius Severus claimed victories against the Parthians, Adiabene (across the Tigris), and Arabs and sacked Ctesiphon and Seleucia in 197 (or maybe January 198). The cites of Rhesaena, Nisibis, and Singara were occupied and given the status of colonies. Abgar VIII was allowed to retain Edessa as part of his client kingdom when Osrhoene became a Roman province [Grant, 229]. Hatra withstood a siege by Severus and Severus could not operate with it behind the lines, so Severus had to retreat from all of Mesopotamia that was further south, but he retained northern Mesopotamia. The triumph of Severus is celebrated on his return to Rome in A.D. 202.

Septimius Severus, 193-211

Septimius Severus, 193-211

Denarius. 19-18 mm. 3.40 grams.

Head right, laureate.

L SEPT SEV PERT AVG IMP V

The obverse of this coin records "IMP V", that is, 5 notable victories of Septimius. The reverse has

PART ARAB PART ADIAB

For victories over the PARThians, ARABs, and ADIABenians.

COS II PP in exegue

Two captives, seated back-to-back, each on a shield

RIC 62 "195". BMC 118. Sear II 6322.

Struck 195.

The arch of Septimius Severus is in the Roman Forum. It was dedicated in 203 AD to commemorate the Parthian victories of Emperor Septimius Severus and his two sons, Caracalla and Geta, in the two campaigns against the Parthians of 194-195 and 197–199 (author photo).

Septimius Severus issued many Parthian victory types (coins). Some of the same types are on coins in the name of his young son Caracalla (coin). However, many coin types of Caracalla's sole reign refer to his own Parthian victories.

Abgar VIII, 179-214, of Edessa, the primary city of "The Kingdom of Osrhoene."

Abgar VIII, 179-214.

Abgar VIII, 179-214.

24 mm. 6.9 grams.

Mint of Edessa.

Bust of Septimius Severus right

CEOVHPO ATOVAP(?)

Severus Autokrater?

Bust of Abgar VIII right in cap

BACIΛЄΩC ABΓAΡOC ["Abgar" begins at 1:00]

BMC Mesopotamia, Edessa 14.

• A.D. 216-217 – Caracalla took advantage of a Parthian civil war between Vologases VI (c. 208-228) and his brother Artabanus IV (c. 216-224). In 216 the Romans invaded and captured the kings of Armenia and Osrhoene (Edessa) and crossed the Tigris without much opposition. The coins celebrating those victories came at the time of Caracalla's twentieth anniversary and often mention "VOT XX" (vows for 20 years) (coins).

Caracalla, sole reign 211-217.

Caracalla, sole reign 211-217.

Denarius. 19 mm. 2.71 grams.

VIC PART PM TRP XX COS IIII PP, Emperor standing left, holding globe and short scepter, being crowned by Victory. Small captive at emperor's feet left.

TRP XX dates the coin to 217, his last year.

RIC 299e. Hill 1600 "R4".

This design also appears on an antoninianus (coin).

Caracalla, sole reign

Caracalla, sole reign

Denarius. 19 mm. 2.93 grams.

VICT PARTHICA

Emperor standing left holding Victory, captives on each side.

RIC 315b. Sear II 6897.

Hill 1602, dates the coin to 217, his last issue. "R4".

Caracalla had his winter quarters in Edessa in 216-217 and was assassinated on the road from Edessa to Carrhae. Macrinus (217-218) succeeded him.

Caracalla introduced the "antoninianus" in a coin reform of 215 (his year 18) and his Parthian victory types are on both denarii and antoniniani (coins).

Vologases VI, Parthian king c. 208-228. There was a long civil war between Vologases VI and his brother Artabanus IV. Caracalla took advantage of the discord to invade. The Parthian brothers finally united in opposition to Caracalla, but the Parthians lost the entire empire to a rebellion of the ruler of Persis (formerly a dependency on the northeast side of the Persian Gulf) who became the first Sasanian ruler, Ardashir I.

Vologases VI, Parthian king c. 208-228.

Vologases VI, Parthian king c. 208-228.

Drachm. 21-19 mm. 3.76 grams.

An extremely crude seated Parthian inspects a bow over a stool. The crude legend on the sides has Greek letters.

Sellwood 88.18.

Shore 455

• A.D. 217 – Caracalla assassinated. In April 217 Caracalla was assassinated on the road from Edessa to Carrhae where he was intending to visit the temple of the local moon god (called "Ba'al Harran" in BMC Greek. "Harran" is another name for "Carrhae").

Caracalla, issued at Edessa.

Caracalla, issued at Edessa.

Small. 19.6 mm. 3.65 grams.

Caracalla's head right, laureate.

M AVR ANTONINIANA AV F AVG (clockwise from 12:30)

Turetted head of Tyche right

COL MET ANTONINIANA AV (clockwise from 12:00)

BMCG Mesopotamia, Carrhae 16-33 (with minor legend variations).

Note: Until 2016 this type was attributed to Carrhae and it still is by dealers. However, an article by Edward Dandrow in the Numismatic Chronicle of 2016 convincingly reattributes this type to Edessa. He notes that the original attribution to Carrhae was made from a single hard-to-read coin in 1828 and uncritically repeated ever since.

Caracalla, issued at Carrhae.

Caracalla, issued at Carrhae.

Small. 17 mm. 3.42 grams.

Radiate head of Caracalla right, legend incomplete with AV AN ... EI

Crescent upwards, with garland below and seven dots within.

KAPKOMΠ (KAP for Carrhae, KO for Colonia, and MΠ for Metropolis)

The crescent for the for cult of the local moon-god.

BMC Greek, Mesopotamia, Carrhae, 14, page 84.

Comment on condition. None of the BMC examples are as legible as this one. Coins from Carrhae usually are in terrible condition with poor original strikes (coin on page 2).

• A.D. 217 – Macrinus. Caracalla was replaced by Macrinus (217-218) who met a severe military reverse outside Nisibis and agreed to pay 5 million [Sartre says 50 million] denarii in exchange for the Parthians allowing Rome to retain Roman Mesopotamia. Nevertheless, Macrinus issued coins claiming a Parthian victory.

Macrinus, 217-218

Macrinus, 217-218

Denarius. 20 mm. 3.02 grams.

IMP C M OPEL SEV MACRINVS AVG

Bust right, laureate and cuirassed.

VICTORIA PARTHICA

Victoria advancing right with wreath and palm.

RIC 97. Sear II 7366.

He also issued another Parthian victory type (coin) and he issued tetradrachms from Carrhae (next) and Edessa. His son, Diadumenian, participates in the provincial issues.

Macrinus, 217-218

Macrinus, 217-218

Tetradrachm from Carrhae.

27.6-24.7 mm. 12.68 grams.

AVT K M OΠCE MAKPINOC CE

ΔΗΜΑΠΧ ΕΞ VΠATOC

Prier 838.

The crescent between the legs of the eagle is a mintmark of Carrhae.

Carrhae had a famous temple of the Moon god, Lunus (a male god), who had some ability to foretell the future. Caracalla was on his way from Edessa to Carrhae to visit the shrine when he was assassinated at the behest of Macrinus who became the next emperor. Prier notes Macrinus many have hurried the assassination for fear the oracle would warn Caracalla. I wonder if Macrinus was especially thankful to Lunus when he minted this coin for Carrhae with the lunar crescent between the legs of the eagle?

It is not always certain which cities issued which tetradrachms. We use the symbols between or below the legs of the eagle to distinguish cities. This crescent issue of Macrinus has a star in the left field and always has him radiate, so there are three astrological symbols on this issue. Attribution to Carrhae, although not completely proven, seems likely.

• A.D. 224-240 Ardashir I (224-240, a.k.a. Artaxerxes) had been the local king of the dependent kingdom of Persis on the northeast coast of the Persian Gulf. He became the first Sasanian king (named after Sasan, an ancestor) by rebelling and defeating the last Parthian kings, Vologases VI and his brother Artabanus IV. Parthian rule was replaced by Sasanian rule. The Parthian ruling class was of central-Asian ancestry and were not "Iranians" (Persians), but Sasanians actually were Iranian (Persian). Ardashir I took Mesopotamia in 230 during the reign of Severus Alexander. Roman provincial coins from northern Mesopotamian cities stopped being issued and did not resume until the region was reconquered by Gordian III (238-244).

Ardashir I, c. 224-242

Ardashir I, c. 224-242

Silver drachm. 26 mm. 4.14 grams.

Bust right, in his distinctive headdress.

"The divine Mazdayasnian King Ardashir, King of Kings of the Iranians."

A flaming fire altar.

"Ardashir's fire"

Sellwood 10.

A tetradrachm is on page 2 (coin).

• A.D. 232 – Severus Alexander (222-235) responded with an indecisive campaign. If there was any victory over the Sasanians it was not enough to cause the resumption of provincial coinage in Mesopotamia. Coins were minted in his name at Edessa before the Parthian invasion.

Edessa, Mesopotamia

Edessa, Mesopotamia

24 mm.

Severus Alexander, 222-235.

AVT K M A CЄVЄ AΛΞANΔ

Autokrater Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander

Radiate bust left with right hand raised in blessing and shield on left shoulder.

(The gesture with the right hand raised is very unusual on Roman coins and this is one of the earliest examples.)

MHT KOΛ ЄΔCCHNωN

(Metropolis, Colony, of Edessa)

City goddess seated left, small altar before, stars to left and right.

Small river god swimming left below.

This coin shows that Edessa was still under Roman control during at least part of the reign of Severus Alexander. The lack of Roman provincial coins from cities of upper Mesopotamia during the reign of Maximinus Thrax (235-238) is evidence that upper Mesopotamia had been lost (to Ardashir I). It was recovered in the time of Gordian III for whom coins were again issued at Edessa, as well as Carrhae, Nisibis, and Singara.

There are Roman imperial coins of Severus Alexander with Victory, but they are not explicit about which victory it is.

Severus Alexader, 222-235.

Severus Alexader, 222-235.

Denarius. 19 mm. 3.08 grams.

VICTORIA AVGVSTI, Victory inscribes shield with VOT/X

which dates this type to 230 or 231.

This date is too early to refer to a victory after Ardashir conquered northern Mesopotamia. BMC Roman VI [p. 75] relates it to preparations for a campaign in the East (coin), that is, not to an actual victory, rather a hoped-for victory.

RIC 219. Sear III 7932.

There are other coins of Severus Alexander that might be related to his Persian war (coin).

• A.D. 241 – Shapur I (241-272, illustrated near the top), son of Ardashir I, invaded Syria in 241. He conqured the Kingdom of Hatra, which had previously remained independent of both Rome and the Sasanians. Shapur I was the Sasanian ruler opposite Gordian III, Philip I, Valerian, and the Kingdom of Palmyra.

• A.D. 242-244 – Gordian III (238-244) was only 13 when he came to the throne. He married Tranquillina and his father-in-law, Timisitheus (no coins are in his name), conducted much of the government. For the Persian war Timisitheus became Pratorian Prefect and he recovered Mesopotamia. So Gordian III is credited with retaking Nisibis and Singara and he issued coins there. First Timistheus died and then the army of Gordian III was defeated and he died (at age 19) north of Ctesiphon (Different ancient sources give different manners of his death). It is likely that treachery of Philip I contributed. Roman imperial coins of Gordian III claim victories, but none have an explicit connection to a victory against Persia.

Gordian III recovered Edessa and installed a client king, Abgar X. Edessa was the city-fortress of the small "Kingdom of Osrhoene [Osroene]".

Gordian III, 238-244

Gordian III, 238-244

32-31 mm. 19.92 grams. "Provincial sestertius"

City of Edessa, Kingdom of Oshroene.

AVTOK K M ANT ΓOPΔIANOC CЄB

Bust of Gordian III, right, laureate

AVTOK ΓOPΔIANOC ABΓAPOC BACIΛЄVS

Gordian III seated right on chair on dais. Abgar standing, wearing tiara, presents Gordian III with Victory.

Sear Greek Imperial 5743 (under the Kingdom of Osrhoene)

BMC Mesopotamia, Edessa 138.

Much later, Edessa was the base for the Persian wars of Constantius II (337-361).

Gordian III minted coins with his wife Tranquillina at Singara and at Nisibis.

Gordian III, 238-244

Gordian III, 238-244

"Provincial sestertius." 33-30 mm.

Struck at Singara. Coins of Singara are scarce and all of them are of Gordian III or Tranquillina.

Gordian III and Tranquillina, facing each other

AVTΟK K M ANT ΓOPΔIANON CAB TPANKVΛΛINA CЄB

Turretted city goddess seated left on pile of rocks, holding ears of grain, small river god swimming left at her feet.

AVP CЄΠ KOΛ CINΓAPA

"CЄΠ" for Septimia, "KOΛ" for "colony" and CINΓAPA for Singara

BMC Greek Mesopotamia Singara 8. Sear Greek Imperial 3804.

RPC on-line 7.2, 3472

Next is a smaller and scarcer denomination from Singara. which explicitly mentions Legion III.

Gordian III, 238-244

Gordian III, 238-244

20 mm. 7.50 grams.

Struck at Singara.

AVTOK K MA ANT ΓOPΔIANOC CЄB

Bust right, laureate, draped and cuirassed, seen from behind.

AVP CЄΠ KOΛ CINΓAPA

Sagittarius galloping right, drawing bow, vexillum behind inscribed ΛЄ/Γ (Legion 3).

Legion III, Parthica, raised by Septimius Severus for his Parthian war.

BMC Greek Mesopotamia Singara --. Sear Greek Imperial --, Lindgren I 2625. BMC --, Weber --, McClean --, Hunterian --, SNG Danish and supplement --, RPC on line 7.2, 3482.

Gordian III, 238-244

Gordian III, 238-244

22 mm. 6.76 grams.

Struck at Carrhae

Radiate head right

AVTOK K M ANT ΓOPΔIANOC CЄB

Crescent moon and two stars

MHTP KOΛ KAPP[HNΩN]

Metropolis Colonia Carrhae (of)

RPC VII.2 3447

Many Mesopotamian coins have astrological references. This remains true of Turkoman figural bronzes from c. 1105-1260.

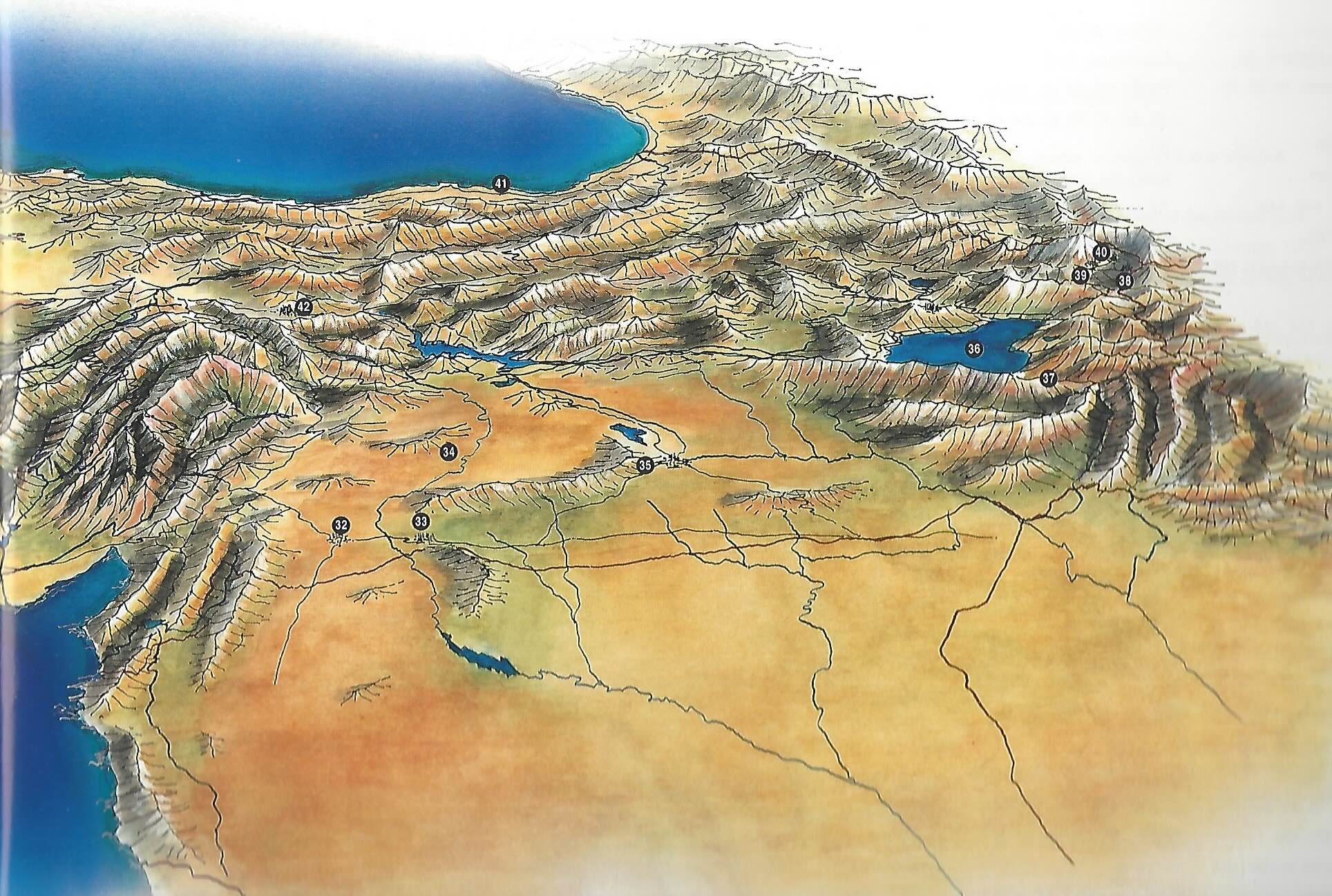

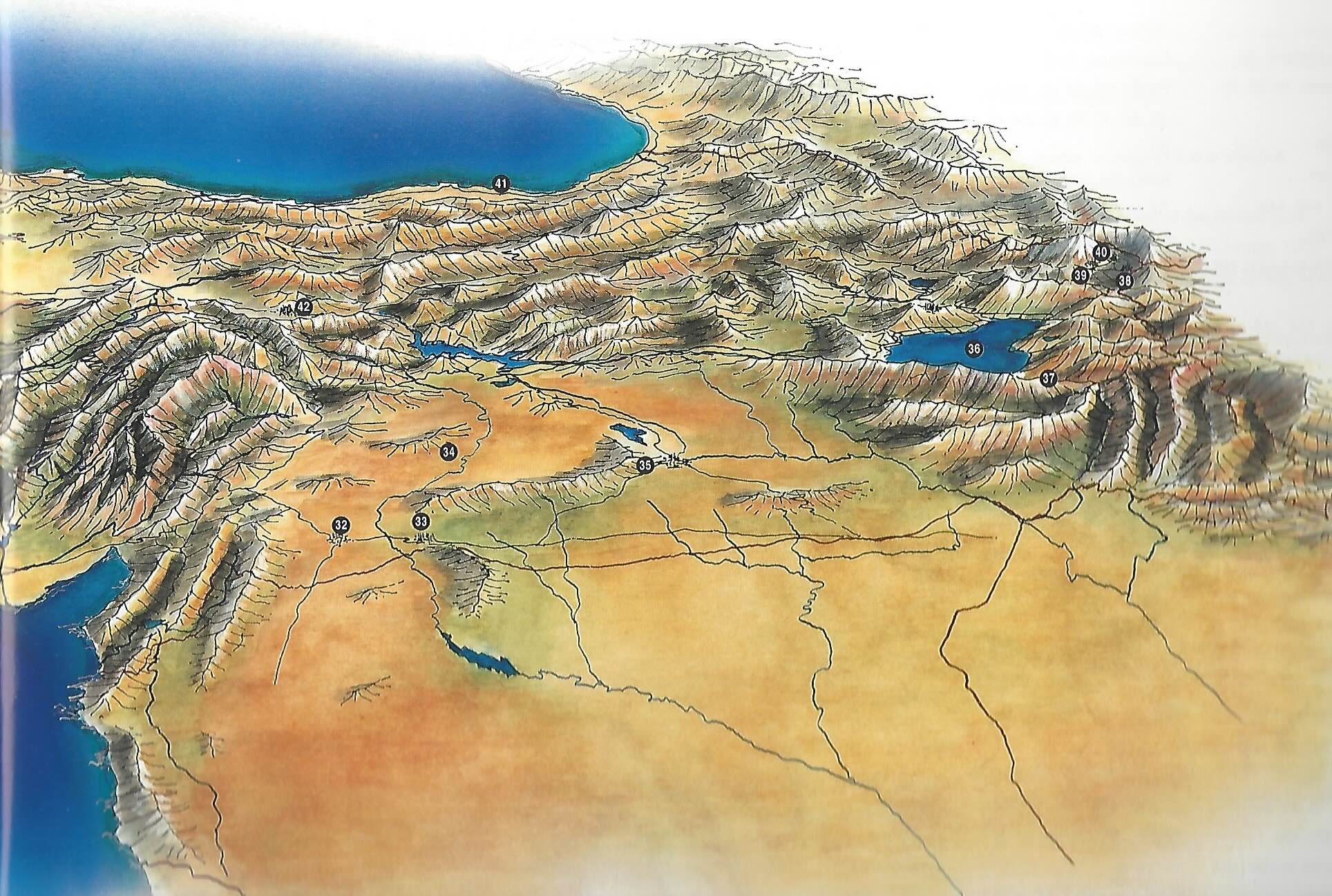

Why are those Roman provincial cities important? Geography plays a huge role. Much of eastern modern-day Turkey is very mountainous--virtually impassible. Take a look at this artist's impression from "Turkey from the Air" by Belge and Yerasimos.

This is not a photograph, but you can see the mountains have a southern edge where east-west travel would be much easier. Cities with water that are close to that line made excellent stops on the "Silk Road." (The numbers on the map refer to modern locations, but not ancient locations. 36 is Lake Van.)

Some Roman imperial coins of Gordian III claim victories and others have vows for a safe return, but none explicitly mention Persia.

• A.D. 244 – Phillip I (244-249) paid the Sasanians 500,000 denarii to buy a safe retreat for the Roman army after Gordian III died. Mesopotamia and Armenia were lost to Shapur I. Nevertheless, Philip issued coins that proclaim "Peace founded with Persia".

Philip I, 244-249

Philip I, 244-249

Antoninianus. 25-22 mm. 4.41 grams.

PAX FVNDATA CVM PERSIS

"Peace founded with Persia"

Pax standing left holding out olive branch with long scepter cradled in left arm.

RIC 69. Sear III 8941.

This is the only imperial type of Philip that mentions Persia.

Philip and his family have common coins from Nisibis (one coin above and a longer separate page about Nisibis).

• A.D. 249-251 – Trajan Decius (249-251) was the last emperor to issue provincial coins from Mesopotamia. They were coins from Rhesaena, which Decius revived after they stopped under Severus Alexander. None of his imperial coins mention Persia.

Trajan Decius (249-251) provincial coin from Rhesaena.

Trajan Decius (249-251) provincial coin from Rhesaena.

25 mm. 12.05 grams.

AYΓK ΓMЄ KY ΔЄKIOC TRAIANO C CЄEB

Bust right, radiate, draped and cuirassed

CЄΠ KOΛ PHCAINHCIωN L...

Tyche in turreted crown with cornucopia and holding patera over flaming altar. Above left an eagle with half-open wings on a palm branch.

Castelin Rhesaena 133, plate X.

It is uncertain why he didn't issue coins from Singara or Nisibis, which were more-important cities.

• A.D. 253-256 – The Sasanians under Shapur I conquered northern Mesopotamia and there is no Roman provincial coinage from that region after Trajan Decius. The Sasanians captured Dura-Europus and overran Syria and occupied Antioch and Tarsos. The Roman historian Zosimus says "The Persians could have conqured all of Asia had they not been overjoyed at their excessive spoils." Probably they realized they could loot, but not occupy for long, a region full of Romans, just as the Romans realized they could loot cities in southern Mesopotamia but not occupy them for long.

• A.D. 253-260 – Valerian spent almost all of his reign in the East. He drove the Sasanians out of Tarsos and Antioch by 256 and issued coins proclaiming RESTITVT ORIENTIS, the restoration of the Orient [Roman East]. (The dates of these events are not certain.) Valerian's attempt in 260 to recapture the cites of northern Mesopotamia failed catastrophically. Ancient sources say that the 70,000 Romans in the army were killed or captured and, famously, Valerian himself was captured alive and spent the rest of his life in captivity. Roman sources say he was humiliated and treated like a slave, but Iranian sources say he was treated honorably. His son and co-emperor Gallienus was too busy dealing with the problems in the rest of the empire to attempt to recover his father and the region.

Valerian, 253-260.

Valerian, 253-260.

21-19 mm. 3.78 grams.

IMP C P LIC VALERIANVS PF AVG

RESTITVT ORIENTIS

Turreted female (The Orient) presenting wreath to the emperor who holds a long staff in his left hand.

RIC 278c. Struck "253-256" Sear III 9967

This type was also issued for his son, Gallineus (coin) and other types of Valerian were issued for Valerian II (coin).

This may be the most ironic type of Roman coin. Valerian's attempt to recover Mesopotamia is one of the most famous Roman deteats.

• A.D. 270ff – After Valerian there seems to have been near-constant warfare in the east. After Shapur I conquered the Roman East, while the Sasanian army was busy in their own eastern regions, Palmyra under its local ruler Odenathus (there are no coins in his name) temporarily occupied Mesopotamia, possibly claiming to act for Gallienus. However, it was a prize not to be given up lightly, so Palmyra attempted independence. Palmyra issued a few rare copper coins. From Antioch there are common coins with Aurelian on one side and Vabalathus (son of Odenathus) on the other. There are also rare coins with Vabalathus alone, and then, after he died, very rare coins of his mother, Zenobia, alone.

Vabalathus, 271-272. The local ruler of Palmyra, Odenathus, recovered some of Mesopotamia from the Sasanaians. When Aurelian prepared to win it back for the central empire, coins were minted with Aurelian as Augustus on the reverse and the son of Odenathus, Vabalathus, on the obverse, as "VCRIMDR" (Next). It is not clear what this abbreviates. Some have accepted the speculation that it abbreviates "Vir Clarissimus, Rex, Imperator, Dux Romanorvm."

Vabalathus, 271-272

Vabalathus, 271-272

21-20 mm.

IMP C AVRELIANVS AVG

Bust of Aurelian right

VABALATHVS VCRIMDR

This coin has an officina number , H (8), below the bust of Aurelian. Normally the officina number is on the reverse, in which case Aurelian would be in the inferior position. Also, the bust of Vabalathus is a tiny bit larger. However, Aurelian does have the title "AVG" which is the superior title.

This type looks like a Roman imperial coin. Also, two-headed tetradrachms were issued from Alexandria, Egypt (coin).

Also, there are coins issued in Roman imperial style in the name of his mother, Zenobia.

Palmyra. Altogether, there are very few coins attributed to Palmyra.

Palmyra, 2nd-3rd C.

Palmyra, 2nd-3rd C.

15 mm. 2.65 grams.

Three busts facing: Baal with polos, the sun god Yarhobol on the left, and the moon god Ayblel on the right,

or, using Roman terms, Serapis in the middle, Sol on the left, and Selene on the right.

ΠAΛMVPA = Palmyra (9:00 to 1:100)

Winged figure holding balance with two pans, over cippus.

Very rare. Coins from Palmyra are not closely dated. Some scholars have suggested they are not coins, rather tokens. Some have suggested this type is a siliqua weight, but it is not the correct weight to serve that function.

A.D. 274 – Aurelian (270-275) recovered Palmyra for the central empire. Aurelian's coins don't explicitly mention Persia, but he does have types referring to victory in the Orient.

Aurelian, 270-275

Aurelian, 270-275

21-19 mm. 3.53 grams.

IMP AVRELIANVS AVG

Buts right, radiate, draped, and cuirassed.

RESTITVT ORIENTIS

Turreted female (The Orient) presenting wreath to the emperor who holds along staff in left.

*T in exergue.

RIC 234 "Siscia". Sear III 11595.

Valerian issued this same reverse (above). Aurelian makes a justified claim to have restored the Roman East (coin).

• A.D. 282-285 – When the Sasanian ruler Bahram I died his son Bahram II (a.k.a. Varhran II) claimed the throne, but so did Bahram's brother Hormazd and his uncle Narses. The Roman emperor Carus (282-283) took advantage of the resulting Sasanian civil war to invade Persia and sack the capitol, Ctesiphon. During the war against Persia Carus died in suspicious circumstances in A.D. 284. Numerian, the younger son of Carus, took over but was murdered on the way back. Diocletian (284-305) took over and withdrew. The Persians recovered Mesopotamia. The cities of northern Mesopotamia had been Roman, but provincial coins were no longer being issued, so we have no city ("provincial") coins from them at this time.

Carinus, the elder son of Carus, who had been holding the central empire, moved east to confront Diocletian but was assassinated while apparently winning a battle with Diocletian, leaving Diocletian sole emperor. The only coins of the period that mention Persia are posthumous coins honoring Carus as DIVO CARO PARTHICO (coin) and DIVO CARO PERS. Some coins of Numerian and Carinus mention Victory, but they do not mention Persia. The brothers have have the only tetradrachms from Alexandria (coins) that mention any specific legion. Whether their coins mentioning the second legion, Traiana, are in any way related to the Persian war is uncertain.

Carus, 282-283. Posthumous. Struck 285 under Carinus.

Carus, 282-283. Posthumous. Struck 285 under Carinus.

24-22 mm. Large. 4.04 grams.

DIVO CARO PERS

Head right, radiate.

CONSECRATIO, eagle standing, head left.

RIC 48, at Rome. Sear III 12396.

This obverse and reverse legend also appear on coins with an altar instead of an eagle.

Consecration coins of Carus and the type of Philip are the only Roman types that use the term "Persia" instead of "Parthia."

Similar coins with the legend DIVO CARO PARTHICO (coin) are more common (and also appear with both an eagle and an altar). Modern historians (but apparently not Romans) limit the term "Parthians" to the rulers before 224 when the Sasanians took over.

Bahram II (Varhan II), 274-293. Under Bahram II the Sasanian empire was far from unified. There were religious disputes, powerful oligarchs who wanted to pursue their own policies, a request for aid against Rome by Zenobia of Palmyra (aid was not forthcoming), and a civil war. The discord allowed Carus to invade Mesopotamia and sack Ctesiphon. Also, Armenia became Roman in 286-288 after having been under Persian influence for many years.

Bahram II, 274-293.

Bahram II, 274-293.

Drachm. 29 mm. 4.30 grams.

Jugate busts right facing a smaller head left.

A flaming fire altar with two attendants.

Sellwood Vahran II type IV.

(More about this coin type).

After Carus coins no longer refer to the wars.

• A.D. 297-298 – Coins of Carus are the last Roman coins to explicitly mention any conflict with Persians. Nevertheless, conflicts continued. Another war followed a Persian invasion of Syria. In the first campaign in 297 Galerius was defeated, but he regrouped and soundly defeated the Sasanian king Narses in a second campaign in 298. Tiridates, protégé of Rome, returned to his Armenian throne and the cities of northern Mesopotamia again became Roman. Roman Mesopotamia remained at its greatest extent, including some territory east of the upper Tigris, until Julian' defeat in 363. However, there is nothing to see of these events on coins. The common follis denomination created in the coin reform of 294 was not topical the way previous Roman types had often been. Peace reigned between Persia and Rome until the end of the reign of Constantine I.

• A.D. 335-337 – Constantine, by supporting Christianity in the Roman Empire, alarmed the Sasanians under Shapur II about their own numerous Christian subjects who might become a pro-Roman fifth column. As with all historical events, there are many "causes" which interacted to explain the subsequent history. [Short explanations in history books (and here) are necessarily oversimplifications.] Constantine spent two years planning a massive invasion of Persia. In 335 he appointed two οf his half-nephews (grandsons of Maximian) as additional Roman rulers. Delmatius became ruler of the lower Danube region and Hanniballianus was to be on the Persian border with the title "Rex regum," king of kings, a Persian title. Clearly he was in line to rule Persia when it was conquered. The Romans did not use the title "king" until this coin type. The type alludes to Persia in two ways--the title and the river god.

Hanniballian, 335-337

Hanniballian, 335-337

17-15 mm. 1.71 grams.

FL HANNIBALLIANO REGI [king]

SECVRITAS PVBLICA

The Euphrates reclining right, holding scepter with urn spilling water and a reed behind.

RIC VII Constantinople 147. (All his coins are from Constantinople.)

Before the invasion got underway, Constantine, on his way to the East, died in May 337 and in the "summer of blood" his sons (especially Constantius II) arranged for all potential rivals to the throne to be eliminated. Delmatius and Hanniballian and other relatives were executed. The invasion was called off.

• A.D. 337-363 – In 337 Shapur II besieged both Nisibis and Singara, but Sasanian coins never mention particular wars. There are remarkable reports of inventive siege techniques used, but neither city was conquered and Shapur II was forced to retreat because the Sasanian empire had been invaded by Chionites from the east. The Chionites were only completely defeated after 20 long years which gave the Roman empire a long period of peace. The conflicts with Persia in the fourth century continued under Constantius II, Julian, and Jovian, but none of their coins have any word for "Persia" on them.

Shapur II invaded Roman Mesopotamia in 359 and forced the Roman army to retreat to Amida, a Roman gateway fortress to Armenia. After after a long and bloody siege, Amida was conquered and several tens of thousands were killed. Julian II prepared a response and invaded Mesopotamia in 362 and the army made it to Ctesiphon before Julian was killed far into Mesopotamia. (Some ancient authors think the fatal strike was by a Christian.) His successor, Jovian, was obliged (by Shapur II) to surrender Rome's former possessions east of the Tigris, as well as Nisibis and Singara, so the Roman army could safely retreat. Shapur soon conquered Armenia, which was abandoned by the Romans. None of these events are explicitly referenced on coins.

Conflicts continue into the Byzantine period, but coins do not tell that story.

Shapur II, Sasanian King.

Shapur II, 309-379.

Shapur II, 309-379.

30 mm. 4.14 grams.

Bust right, with Shapur II in a distinctive crown.

Fire altar, with head right in flames and two attendants.

Sellwood 32.

No Sasanians coins explicitly mention victories.

Constantius II, 337-361. The closest that fourth-century Roman coins come to acknowledging the conflicts with Persia is the fallen horseman who sometimes has Persian attributes on the FEL TEMP REPARATIO "soldier spearing fallen horseman" type:

Constantius II, 337-361.

Constantius II, 337-361.

25-23 mm.

The coin does not mention Persians, but the reverse has a figure that reminds us of Persians. The soldier is spearing

1) a horsemen

2) who is bearded, and

3) wearing trousers

Except for the horse, he could be a northern barbarian, but the horse tips the identification toward a Persian.

FEL TEMP REPARATIO, soldier spearing fallen horseman

ANE for the Antioch mint.

RIC VIII Antioch 132.

The other FEL TEMP REPARATIO types with captives lack the horse and likely refer to victories elsewhere.

Julian II, the Apostate.

Julian II, Caesar 355-360 and Augustus 360-363.

Julian II, Caesar 355-360 and Augustus 360-363.

28-27 mm.

SECVRITAS REIPVB

Bull right, two stars above. The bull may be a reference to pagan rites.

<palm>NIKB<palm> in exergue, for Nicomedia.

Bust right, cuirassed and draped. Julian II has a long philosopher's beard illustrating his adherence to the old gods and opposition to Christianity.

RIC VIII Nicomedia 121. Sear V 19159.

No coins of Julian II or Jovian make any explicit reference to the Persian war.

Still later, 363-628. Sasanian king Shapur III (383-388) ceded some territories in Armenia back to the Romans. Emperor Arcadius thought highly of the Sasanian king Yazdigerd (399-420) and sent Theodosius II (402-450) as a child to be tutored in Ctesiphon [F 208]. Conflicts continued under Byzantine emperors including Anastasius, Justinian, Justin II, and Heraclius (610-641). The Sasanian empire was extinguished by the Arabs in a long series of battles 632-651. Northern Mesopotamia was never Roman again.

Skip down to all the timeline notes in one place.

Cities of northern Mesopotamia (See the map at the top): Edessa, Carrhae, Rhesaena, Nisibis (Nesibi on coins), and Singara. (Respectively, now Şanlıurfa in Turkey, Harran in Turkey, Ra's al-'Ayn in Syria, Nusaybin in Turkey, and Sinjar in Iraq. All are close to the modern Turkish border.) Think of these as typical garrison towns. These cities have no coins of Maximinus Thrax (235-238) because they were conquered by the Persians during the reign of Severus Alexander (222-235) and not recovered until the reign of Gordian III (238-244).

Edessa: Edessa issued more coins than other Mesopotamian cities. It issued silver denarii under Marcus Aurelius, Faustina II, and Lucilla. From 179 through Severus Alexander, it issued bronze with imperial portraits and coins with portraits of local rulers of "the Kingdom of Osrhoene." The city was apparently lost under Severus Alexander and regained by Gordian III who issued coins both with and without a local ruler on the reverse. After no coinage under Philip, Trajan Decius issued coins there--the last Roman ruler to do so. Tetradrachms of Syrian fabric are attributed to Edessa for Caracalla, Macrinus, and Diadumenian.

Carrhae (a.k.a. Harran): Carrhae issued coins from Marcus Aurelius to Gordian III. It was lost to Shapur I c. 230 and recovered for Rome by Gordian III from Shapur I at the Battle of Rheseana in 243 [wikipedia], which also recovered Nisibis, and Singara. Most coins of Carrhae are very poorly produced. Tetradrachms of Syrian fabric are attributed to Carrhae for Caracalla, Macrinus, and Diadumenian. It has no coins of Maximinus (235-238).

Rhesaena: Rhesaena (Rhesaina) was made a colony by Septimius Severus, although its coins begin with Caracalla or Elagabal (They are hard to tell apart). There are also coins of Severus Alexander. The are no coins for Macrinus or Gordian III. They resume with a large issue under Trajan Decius (249-251), the last emperor to issue coins from Rheseana. They are in low relief and almost always very worn. Tetradrachms of Syrian fabric are attributed to Rhesaena for Caracalla. Legion I Parthia was stationed there through the time of Constantius II. The ruins cover more than a square mile.

Nisibis: When under Roman control it was the capitol of Roman Mesopotamia. Nisibis was made a Roman colony under Septimius Severus (hence the title ϹƐΠ for "Septimia" seen on some of its coins), but Roman provincial coins did not begin until Macrinus (217-218). They are scarce through Gordian III (238-244). Then they are common under emperor Philip (244-249) and his family, Philip II and Otacilia Severa--the last Romans to issue coins from Nisibis. Nisibis was probably lost to the Sasanians c. 250-252 which explains why Roman provincial coinage from Mesopotamia ceased then. Here is my page about coins of Nisibis.

Singara: Singara was made of colony of veterans by Septimius Severus. The coins of Singara all belong to the reign of Gordian III (sometimes with his wife, Tranquillina). Singara was recovered for Rome under Gordian III by the Battle of Rhesaena in 243. Singara was a colony of veterans. The number of the third Parthian legion appears on some of its coins.

Anthemusia: Anthemus(ia) was founded by Macedonians and named after a Macedonian city. It plays almost no role in the history books. BMC Greek Mesopotamia has only two coins, both under Caracalla, who may have visited the place during his campaign.

Other regions under contention. Armenia, the region north of northern Mesopotamia, was not fully independent in this period, rather it had a king approved or appointed by either Rome or Persia. Be careful, ancient Armenia is not in the same place as medieval Armenia (The Seljuq conquest of eastern Turkey caused the Christian Armenians to move south to Cilicia). Similarly, there were other "buffer" states that were not quite Roman and not quite Persian. There were semi-independent fortified cities and their surroundings, including at times, Hatra, Palmyra, and the Kingdom of Osrhoene around Edessa.

Rome and Persia had wars with each other, but do not think that conducting wars with each other were all that the armies were doing. They had only one relatively short border to dispute and other very long borders to protect and possibly extend. Think of a map of the Roman empire and note how short the border with Parthia/Persia is when compared with the Rhine and Danube frontiers, not to mention North Africa and Britain. Think of a map of Iran and Iraq (approximately the region of Persia) and how short the border with Rome is compared to the long northern and eastern borders. Sometimes preoccupations with other borders or civil wars weakened the defense of their joint border and made incursions by the other side inviting. For example, the Parthians took advantage of the civil war between Septimius Severus and Pescennius Niger to take Adiabene and Armenia and to invade Syria and Cappadocia. The Romans under Caracalla took advantage of the Parthian civil war between Vologases V (191-208) and Ardabanus IV (216-224). Carus took advantage of a civil war between Bahram II and his uncle Narses. But often the attention of both empires was elsewhere. For example, there was peace during the whole reign of Commodus (180-193).

Comments. Several emperors not listed on the page issued coins with a reverse design with Sol and the legend ORIENS AVG. I have chosen to omit them because I regard them as religious and not as a direct reference to a Persian war. The fact they were issued by emperors like Postumus in Gaul and Allectus in Britain supports the inference they are not about Persian wars.

Parthia.com has everything about coins of Parthia. For a complete list of Parthian-related Roman coins, including those that only mention Parthia in the obverse legend, see its page: https://parthia.com/parthia_coins_rome.htm (Roman coins are mostly not illustrated or discussed).

The Sasanians minted coins in many cities and gave them mintmarks we can identify, but they did not mint coins in any cities of northern Mesopotamia, so Sasanian coins do not tell us when northern Mesopotamia was occupied by the Sasanians.

References are on another page.

Timeline. Key to the links: Links from names are to coins illustrated on this page.

Links labeled "(coin)" are to coins illustrated on a second page.

[These comments are all repeated from above. This is merely to put all the history in one place uninterrupted by images.]

• 53 B.C. - A.D. 115 – Roman armies suffered famous disastrous losses in Persia under Crassus at Carrhae in 53 B.C. and under Marc Antony in 36 B.C. In 20 B.C. Augustus recovered the lost standards by diplomacy, not by war. In A.D. 58 under Nero the Roman army replaced the pro-Parthian ruler of Armenia while the main Parthian forces were fighting elsewhere, but in 62 the Parthians struck back and reversed all the gains. Then a compromise allowed both sides to keep a hand in Armenia and served to keep the peace for 50 years until the time of Trajan. This web page emphasizes coins of Trajan and later.

Trajan and later:

• A.D. 115-118 – Trajan installed a pro-Roman King in Armenia and invaded Mesopotamia. Its capitol Ctesiphon was sacked in 117. When Trajan invaded Parthia he brought along a Parthian prince, Parthamaspates, who had been in exile in Rome to install as puppet ruler. It proved impossible to occupy Persia for long, so his successor Hadrian withdrew from most of Mesopotamia. No Roman provincial coins were issued in Mesopotamia until Marcus Aurelius. (Here is a short page on related coins of Trajan.)

• A.D. 117 – Hatra withstood a siege by Trajan. It was a large Arab caravan city with more than four miles of walls and 160 defensive towers.

• A.D. 161-166 – Lucius Verus led a war against Parthia under king Vologases IV (c. 147-191, sometimes spelled "Valaksh"). In 162 Vologases IV had installed a pro-Parthian ruler in Armenia and conquered the fortress-city of Edessa, seat of the Kingdon of Osrhoene. In response, Verus first successfully invaded Armenia and in 163 installed his own pro-Roman ruler, to cover his northern flank, and then invaded all of Mesopotamia and sacked Seleucia and Ctesiphon. (Actually, his generals did it while Verus enjoyed the delights of Antioch). Dura-Europos (overlooking the Euphrates from the west) was captured and occupied by the Romans, ending Parthian control. It was recaptured in 241 by Shapur I (241-272). Dura-Europos did not issue coins, but archaeology has found many written records there that illuminate our understanding of the Roman/Persian borderlands. Whether any of the rest of northern Mesopotamia remained occupied by the Roman army is uncertain.

• A.D. 165 – A severe plague broke out among the army at Seleucia which forced Roman withdrawal. The soldiers brought the plague back to the Roman empire where it caused very many deaths. Parthia suffered similarly from the plague. Upon the return of Lucius Verus return to Rome he shared his triumph with Marcus Aurelius (coin).

• A.D. c. 193 – Vologases V (c. 191-208) took advantage of the civil war between Pescennius Niger and Septimius Severus to take Adiabene and Armenia. Then internal revolts against Parthian rule left Vologases V unable to concentrate on the Roman response.

• A.D. 195-199 – Septimius Severus campaigned against Parthia under king Vologases V. Septimius Severus claimed victories against the Parthians, Adiabene (across the Tigris), and Arabs and sacked Ctesiphon and Seleucia in 197 (or maybe January 198). The cites of Rhesaena, Nisibis, and Singara were occupied and given the status of colonies. Abgar VIII was allowed to retain Edessa as part of his client kingdom when Osrhoene became a Roman province [Grant, 229]. Hatra withstood a siege by Severus and Severus could not operate with it behind the lines, so Severus had to retreat from all of Mesopotamia that was further south, but he retained northern Mesopotamia. The triumph of Severus is celebrated on his return to Rome in A.D. 202.

A.D. 200-363. Key to the links: Links from names are to coins illustrated on this page.

Links labled "(coin)" are to coins illustrated on a second page.

• A.D. 216-217 – Caracalla took advantage of a Parthian civil war between Vologases VI (c. 208-228) and his brother Artabanus IV (c. 216-224). In 216 the Romans invaded and captured the kings of Armenia and Osrhoene (Edessa) and crossed the Tigris without much opposition. The coins celebrating those victories came at the time of Caracalla's twentieth anniversary and often mention "VOT XX" (vows for 20 years) (coins).

• A.D. 217 In April 217 Caracalla was assassinated on the road from Edessa to Carrhae and replaced by Macrinus (217-218) who met a severe military reverse outside Nisibis and agreed to pay 5 million [Sartre says 50 million denarii] in exchange for the Parthians allowing Rome to retain Roman Mesopotamia. Nevertheless, Macrinus issued coins claiming a Parthian victory.

• A.D. 224-240 – Ardashir I (the first Sasanian king, a.k.a. Artaxerxes) defeated the last Parthian kings, Vologases VI and his brother Artabanus IV, ending the Kingdom of Parthia and replacing it with Persia under the Sasanians. After this it becomes proper to call the foes of Rome "Persians."

• A.D. 230-231 – Ardashir I took Mesopotamia during the reign of Severus Alexander. Roman provincial coins from northern Mesopotamian cities stopped being issued and did not resume until the reign of Gordian III (238-244).

• A.D. 232 – Severus Alexander responded with an indecisive campaign. If there was any victory over the Sasanians it was not enough to cause the resumption of provincial coinage in Mesopotamia.

• A.D. 241 – Shapur I (241-272), son of Ardashir I, invaded Syria in 241. The Kingdom of Hatra, which had previously remained independent of both Rome and the Sasanians, was conquered by Shapur I.

• A.D. 242-244 – Gordian III (238-244) was only 13 when he came to the throne. He married Tranquillina and his father-in-law, Timisitheus (no coins are in his name), conducted much of the government. For the Persian war Timisitheus became Pratorian Prefect and he recovered Mesopotamia. So Gordian III is credited with retaking Nisibis and Singara and he issued coins there. First Timistheus died and then the army of Gordian III was defeated and he died (at age 19) north of Ctesiphon (Different ancient sources give different manners of his death). It is likely that treachery of Philip I contributed. Roman imperial coins of Gordian III claim victories, but none have an explicit connection to a victory against Persia.

• A.D. 244 – Phillip I paid the Sasanians 500,000 denarii to buy a safe retreat for the Roman army after Gordian III died. Mesopotamia and Armenia were lost to Shapur I. Philip issued coins that proclaim "Peace founded with Persia".

• A.D. 249-251 – Trajan Decius was the last emperor to issue provincial coins at Rhesaena, having revived them after they stopped under Severus Alexander. None of his imperial coins mention Persia.

• A.D. 253-256 – The Sasanians under Shapur I conquered northern Mesopotamia and there is no Roman provincial coinage from that region after Trajan Decius. The Sasanians captured Dura-Europus and overran Syria and occupied Antioch and Tarsos. The Roman historian Zosimus says "The Persians could have conqured all of Asia had they not been overjoyed at their excessive spoils." Probably they realized they could loot, but not occupy for long, a region full of Romans, just as the Romans realized they could loot cities in southern Mesopotamia but not occupy them for long.

• A.D. 253-260 – Valerian spent almost all of his reign in the East. He drove the Sasanians out of Tarsos and Antioch by 256 and issued coins proclaiming RESTITVT ORIENTIS, the restoration of the Orient [Roman East]. (The dates of these events are not certain.) Valerian's attempt in 260 to recapture the cites of northern Mesopotamia failed catastrophically. Ancient sources say that the 70,000 Romans in the army were killed or captured and, famously, Valerian himself was captured alive and spent the rest of his life in captivity. Roman sources say he was humiliated and treated like a slave, but Iranian sources say he was treated honorably. His son and co-emperor Gallienus was too busy dealing with the problems in the rest of the empire to attempt to recover his father and the region.

• A.D. 270ff – After Valerian there seems to be near-constant warfare in the east. While the Sasanian army was busy in their eastern regions, Palmyra under its local ruler Odenathus (there are no coins in his name) temporarily occupied Mesopotamia. Palmyra issued a few rare copper coins. From Antioch there are common coins with Aurelian on one side and Vabalathus (son of Odenathus) on the other. There are also rare coins with Vabalathus alone, and then, after he died, very rare coins of his mother, Zenobia, alone. Palmyra was recovered for the central empire by Aurelian, who issued RESTVTIT ORIENTIS coins.

• A.D. 282-285 – When the Sasanian ruler Bahram I died his son Bahram II (a.k.a. Varhran II) claimed the throne, but so did Bahram's brother Hormazd and his uncle Narses. The Roman emperor Carus took advantage of the resulting Sasanian civil war to invade Persia and sack the capitol, Ctesiphon. During the war against Persia Carus died in suspicious circumstances in A.D. 284. Numerian, the younger son of Carus, took over but was murdered on the way back. Diocletian took over and withdrew. The Persians recovered Mesopotamia. Carinus, the elder son of Carus, who had been holding the central empire, moved east to confront Diocletian but was assassinated while apparently winning a battle with Diocletian, leaving Diocletian sole emperor. The only coins of the period that mention Persia are posthumous coins honoring Carus as DIVO CARO PARTHICO (coin) and DIVO CARO PERS. Some coins of Numerian and Carinus mention Victory, but they do not mention Persia. The brothers have have the only tetradrachms from Alexandria (coins) that mention any specific legion. Whether their coins mentioning the second legion, Traiana, are in any way related to the Persian war is uncertain.

Here is a table which gives the Persian ruler at the time of each of these Roman emperors. It includes a few comments.

Later: After coins no longer refer to the wars:

• A.D. 297-298 – Coins of Carus are the last Roman coins to explicitly mention any conflict with Persians. Nevertheless, conflicts continued. Another war followed a Persian invasion of Syria. In the first campaign in 297 Galerius was defeated, but he regrouped and soundly defeated the Sasanian king Narses in a second campaign in 298. Tiridates, protégé of Rome, returned to his Armenian throne and the cities of northern Mesopotamia again became Roman. Roman Mesopotamia remained at its greatest extent, including some territory east of the upper Tigris, until Julian' defeat in 363. However, there is nothing to see of these events on coins. The common follis denomination created in the coin reform of 294 was not topical the way previous Roman types had often been. Peace reigned between Persia and Rome until the end of the reign of Constantine I.

• A.D. 335-337 – Constantine, by supporting Christianity in the Roman Empire, alarmed the Sasanians under Shapur II about their own numerous Christian subjects who might become a pro-Roman fifth column. As with all historical events, there are many "causes" which interacted to explain the subsequent history. [Short explanations in history books (and here) are necessarily oversimplifications.] Constantine spent two years planning a massive invasion of Persia. In 335 he appointed two οf his half-nephews (grandsons of Maximian) as additional Roman rulers. Delmatius became ruler of the lower Danube region and Hanniballianus was to be on the Persian border with the title "Rex regum," king of kings, a Persian title. Clearly he was in line to rule Persia when it was conquered. The Romans did not use the title "king" until his coin type.

Before the invasion got underway, Constantine, on his way to the East, died in May 337 and in "the summer of blood" his sons (especially Constantius II) arranged for all potential rivals to the throne to be eliminated. Delmatius and Hanniballian and other relatives were executed. The invasion was called off.

• A.D. 337-363 – In 337 Shapur II besieged both Nisibis and Singara, but Sasanian coins never mention particular wars. There are remarkable reports of inventive siege techniques used, but neither city was conquered and Shapur II was forced to retreat because the Sasanian empire had been invaded by Chionites from the east. The Chionites were only completely defeated after 20 long years which gave the Roman empire a long period of peace. The conflicts with Persia in the fourth century continued under Constantius II, Julian, and Jovian, but none of their coins have any word for "Persia" on them. The closest that fourth-century Roman coins come to acknowledging the conflicts with Persia is the fallen horseman who sometimes has Persian attributes on the FEL TEMP REPARATIO "soldier spearing fallen horseman" type (below).

Shapur II invaded Roman Mesopotamia in 359 and forced the army to retreat to Amida, a Roman gateway fortress to Armenia. After after a long and bloody siege, Amida was conquered and several tens of thousands were killed. Julian II prepared a response and invaded Mesopotamia in 362 and the army made it to Ctesiphon before Julian was killed far into Mesopotamia. (Some ancient authors think the fatal strike was by a Christian.) His successor, Jovian, was obliged (by Shapur II) to surrender Rome's former possessions east of the Tigris, as well as Nisibis and Singara, so the Roman army could safely retreat. Shapur soon conquered Armenia, which was abandoned by the Romans. None of these events are explicitly referenced on coins.

• A.D. 363-628. Sasanian king Shapur III (383-388) ceded some territories in Armenia back to the Romans. Emperor Arcadius thought highly of the Sasanian king Yazdigerd (399-420) and sent Theodosius II (402-450) as a child to be tutored in Ctesiphon [F 208]. Conflicts continued under Byzantine emperors including Anastasius, Justinian, Justin II, and Heraclius (610-641). The Sasanian empire was extinguished by the Arabs in a long series of battles 632-651. Northern Mesopotamia was never Roman again.

Caveats. Ancient literary sources are sparse. Many of the events are not well-documented and the surviving accounts clearly "spin" their motivations. Many of the dates are not explicitly given but are inferred from inadequate sources; many dates could be off by a year or more. Concise statements about Roman history are likely to be oversimplifications. History is complex. So, don't be sure every "fact" is the truth. (E.g. Did Shapur I reign 240-270 or 241-272? Did Valerian have his early success in 254 or as late as 256?)

Parthian and Sasanian names are spelled various ways in English. I have used the spelling used in most numismatic reference works, but other spellings may be seen in history books.

Parthian coins are difficult to attribute to issuing emperors. Very few types have a distinguishing name anywhere in the legend. Some scholars have recently reattributed types to new kings that had long been given to different kings. I use the old attributions of Sellwood and Shore. Sasanian coins are easy to attribute to emperors and mints, but have no topical references and their mints are never in a region under dispute (unlike Roman-provincial-coin mints).

Both Rome and Persia supported buffer client states, so it is not quite right to envision a map with "Rome" and "Persia" and a border between them. For example, Armenia (north of northern Mesopotamia), was a major client state with a ruler approved of or appointed by one side or the other. It is not quite Roman and not quite Persian either. Also, when Rome sacked the capitol, Ctesiphon, it may give the erroneous impression that all of Persia was defeated, but most of Persia was east of the Tigris and Mesopotamia was not its main region. It is perhaps best to think of Parthia and Persia as primarily the region of modern Iran, with southern Mesopotamia (Iraq) as its westernmost region. The Persian army was more often occupied on its northern and eastern borders than against Rome, just as the Roman army was more often occupied on the Danube and Rhine borders.

Also, we might look at a map and think all the area is created equal, but that is far from so. Only cities and narrow regions alongside the rivers were of much significance. The rest was desert, not fertile, and barely occupied. Control of rivers (e.g. as Dura-Europos provided) and especially junctions of rivers was important.

Go to page 2 with additional photos and comments.

Here is a table which gives the Persian ruler at the time of each of these Roman emperors. It includes a few comments.

Go to the Table of Contents of this entire educational site.

First posted, 2023, Feb. 5.

Macrinus, 217-218

Macrinus, 217-218