The mintmarks of Antioch = Theopolis (= Theoupolis)

under the Byzantine emperor Justinian, 527-565 AD.

Most Byzantine mint cities had a single clear mintmark, such as "CON" for Constantinople. However, Antioch had more than a dozen very different mintmarks under Justinian. (An illustrated list of the mintmarks is far below.) The city had two distinct names. After catastrophic earthquakes of AD 526 and 528 it changed its name to Theopolis ("City of God"). The earthquakes of February 2023 were similar. (I added Antioch to this map from the New York Times of the Feb. 2023 earthquake.) The tragic history of Antioch is below.

Most Byzantine mint cities had a single clear mintmark, such as "CON" for Constantinople. However, Antioch had more than a dozen very different mintmarks under Justinian. (An illustrated list of the mintmarks is far below.) The city had two distinct names. After catastrophic earthquakes of AD 526 and 528 it changed its name to Theopolis ("City of God"). The earthquakes of February 2023 were similar. (I added Antioch to this map from the New York Times of the Feb. 2023 earthquake.) The tragic history of Antioch is below.

What's new? 2025, August 29: Better examples of Sear 217 and 225.

2025, June 3: Mintmarks listed with links to images (next).

2025, March 24: A coin from year 37 with a blundered obverse legend.

2025, Feb. 24: The type of Justin II which immediately follows the last type of Justinian.

2025, Feb. 23: An example of year 35, the year in which the obverse legend began to be illegible.

Mintmarks: ANTIX, ANTX, +THEUP+, θYΠOΛS, θVΠO, θV, CHEUPo, CH, ɥHɥΠo/, THUΠ/, THUP, THUP*, THEUP, P.

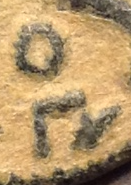

Mintmarks that are arranged vertically:

AN , T H , θY , o

TX E U ΠO Π/

o ΛS

P

The first mintmarks under Justinian were ANTIX and ANTX, which resembles our spelling, Antioch, but with "X" (a Greek chi, for the "ch" sound) at the end because it is really in Greek (and the "O" is arbitrarily omitted). Only the first year of Justinian's long reign continued the ANTIX mintmark commonly seen under Justin I.

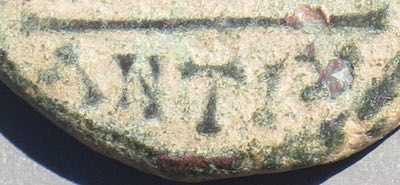

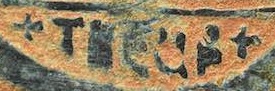

ANTIX

ANTIX

Sear 213

Follis. 29 mm. 14.42 grams.

Officina A

This ANTIX mintmark was used only

at the beginning of Justinian's

reign and not after the

earthquake of 528.

Antioch was primarily a Greek-speaking city and the "X" of "ANTIX" is a Greek chi, which gives the "CH" sound in Antioch. But the mintmark ANTIX is rare under Justinian (but not rare earlier) and did not last long.

ANTX

ANTX

Sear 233

Sear 233

Struck 527-529

25-22 mm. 6.61 grams.

B CON-CORDI around (officina B)

I (for 10 in Greek) surmounted by cross

ANTX in exergue.

MIBE I Justinian N137 (not in the first edition)

DOC I (204) [Parentheses mean they knew about the type but it was not in their colletion at the time]

This flan is larger than flans of later decanummia.

ANTX is a common mintmark for Justin I (518-527) at Antioch. For Justinian, it is found only on this denomination and type.

The Great Variety of Mintmarks for One City: Antioch was renamed "Theopolis" after the first year of Justinian's reign. The mintmarks from the first year refer to Antioch and mintmarks from the following 37 years under Justinian refer to Theopolis. (Yes, he ruled a long time!) Mintmarks are discussed and their coins illustrated following the story of the name change. An illustrated list of the mintmarks is far below.

If you want to skip the story and just see illustrations of the coins, scroll down a bit or click here.

The Tragic Story of Antioch. The city had been the capital of Syria and one of the three major eastern cities of the empire (Constantinople, Antioch, and Alexandria), but on May 29 of 526, about a year before the reign of Justinian began, an extremely violent earthquake hit which destroyed most of the buildings and the subsequent fire destroyed most of the rest. Reportedly 250,000 people died. Antioch never really recovered, nor did the disasters cease.

On November 29 of 528, about two years later and a year after Justinian's reign began August 1, 527, Antioch was again hit by a powerful earthquake which killed another 5,000 of the already-reduced population. After this the remaining hopeful and fearful population renamed it "Theopolis" (less frequently spelled "Theoupolis"), the "City of God." Thereafter, coin mintmarks referenced the new name. (Antioch is on an earthquake fault; Cassius Dio wrote about an earthquake during Trajan's reign,)

Procopius, an ancient author, noted that in 536 "a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during the whole year, … and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear." This is confirmed by other ancient authors and even by tree-ring analysis. A volcanic eruption (which volcano has not been identifed. One in Iceland has been proposed) pumped massive amounts of pollutants into the atmosphere which reduced sunlight for more than a year which caused crops to fail and famines worldwide.

In 540 (year 13), the Sasanian emperor Khusru I (Chosroes) sacked the somewhat restored city of Antioch (Here is a quote from Procopius about it), burned all but the suburbs, and took captive those he did not manage to kill, eventually using the captives to populate a city, "Antioch of Khusru," which he founded on the Tigris a day's distance from Ctesiphon. Only a year later, in 541, (year 14) Antioch, and much of the rest of the empire, was hit by a devastating plague which was so severe that at its height it killed thousands a day in Constantinople and which returned three more times in that generation. Not only was Antioch decimated, but so was the whole empire. There were again earthquakes in 551 and 557. Byzantine coinage from Antioch ceased in 610 under Phocas when it was temporarily occupied by the Sasanians. Byzantine Antioch ended in 637 when it was conquered by the Arabs.

Coins while the city was still named "Antioch". The follis is the first coin on this page. The half-follis (20-nummi) coins had the city name spelled on either side of a long cross.

Sear 224A variety. (He notes only officina A and gamma, but this one is B.)

Sear 224A variety. (He notes only officina A and gamma, but this one is B.)

20-nummi

27-26 mm. 8.23 grams.

DN IVSTINI-ANVS PP AVG

A N

T X across a long cross (does the cross serve as the "I"?)

The style of this piece is as good as most Byzantine coins of the period. It is from before the second earthquake.

BMC --, MIBE (Hahn) 132B. DO --.

MIBE 133 clearly has TI-X where this one has T-X. The DOC example is poor with the supposed "I" invisible and may actually be this type.

Here is a second example:

Sear 224A

Sear 224A

Half-follis. 20 nummi.

27-23 mm. 7.17 grams.

A N

T X across cross.

The quality of the obverse lettering is not as good as on the previous coin.

Struck before the second earthquake of 528.

DN IVSTINIANVS PP AVG

MIBE (Hahn) 132, this coin.

The next two are irregular, blundered, full-sized folles intended to be like the first coin on this page.

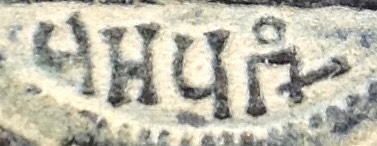

ANTIX

An imitation of Sear 213

Follis.

35 mm. (remarkably large -- at is broadest 5 mm larger than official coins), 14.99 grams, (full weight for the type) 6:00 die axis.

ANTIX mintmark very clear.

The obverse legend is blundered, with S written retrograde

and legend that looks like

DIN ISTINIANOYS

The large size and full weight suggest this was made to supply a need for coinage, as opposed to illegal production for profit.

ANTIX

ANTIX

Another imitation of Sear 213, however with a cresent right.

Follis. 35-30 mm. (remarkably large) 15.30 grams, (full weight for the type) 5:30 die axis.

ANTIX mintmark clear.

Officina gamma.

The obverse legend is blundered, with S written retrograde twice (and forward once)

and legend that looks like

DN IVSTINSVIS PP AVGS

This and the previous blundered coin suggest that the demand for coin dies could not be supplied by literate engravers at the mint. Maybe they were killed in or displaced by the first earthquake, although there are some coins of this type and the next that are of good style and spelled correctly (above). However, the heavy weights of these two do not suggest an attempt to profit by issuing lighter coins. I don't see how we can know, but I think these are official mint products from Antioch at a time of extreme stress. Bates suggests the mal-formed letters might have been intentional as retaliation for Justinian's persecution of paganism and heresies at Antioch [p. 74].

There are 10-nummi pieces, but no 5- or 1- nummi pieces, with a variant of "Antioch" for a mintmark.

After the Second Earthquake. After the second earthquake Antioch was renamed "Theopolis"-- THEOUPOLIS ("City of God"). Mintmarks exhibit the new name. At first the profile bust is retained.

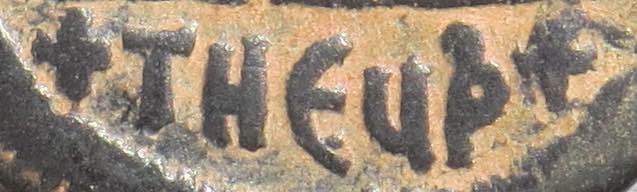

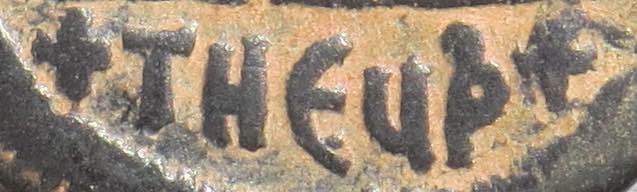

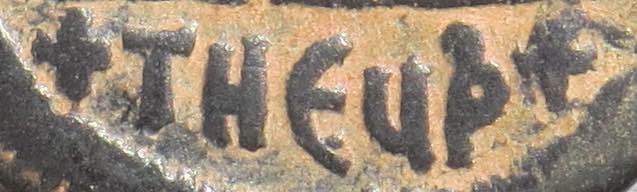

+THEUP+ (Small o above the P)

Sear 216

Follis.

31-28 mm. 13.52 grams.

Profile bust.

+THEUP+ (Small o above the P)

Struck 529-531 [Hahn, MIBE 126. DO 210d]

This profile bust was discontinued in year 13,

which began the facing bust series (below) at Antioch.

+THEUP (no small "o" and the terminal "+" omitted)

+THEUP (no small "o" and the terminal "+" omitted)

Another Sear 216

Follis. 31-30 mm. 11.68 grams. 6:00.

The reverse is odd for having a bent "M".

How can that be? The usual explanation would be a sliding or double strike,

but the mintmark is clear and well-struck only once.

If you collect Byzantine copper you must find enjoyment in such oddities, because there is little beauty or perfection to be seen.

Another Sear 216, this one is an imitation.

Another Sear 216, this one is an imitation.

Follis. 30-28 mm. 11.97 grams. 6:00.

The previous coin with the bent M nevertheless has obverse lettering that looks official.

In contrast, this coin has a legend with a backwards "S" and incomplete name:

DN IVSTI[N?] ANV[no "S"] PP AV[G?]

The reverse is also crude, with the middle of the M oddly extended downward.

Officina Γ

+THEUP+ with a small "o" above the P.

After two earthquakes the mint was having trouble. This example has the 6:00 die axis of official pieces, but does not look official. Is it a local imitation to provide coins that the mint did not, or is it an incompetent attempt to make an official coin by a stressed mint?

[This ugly coin had bronze disease and was completely stripped. Now it is toning back a bit.]

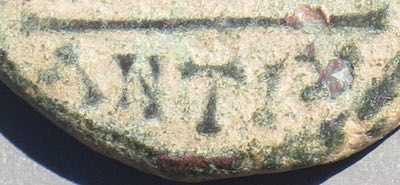

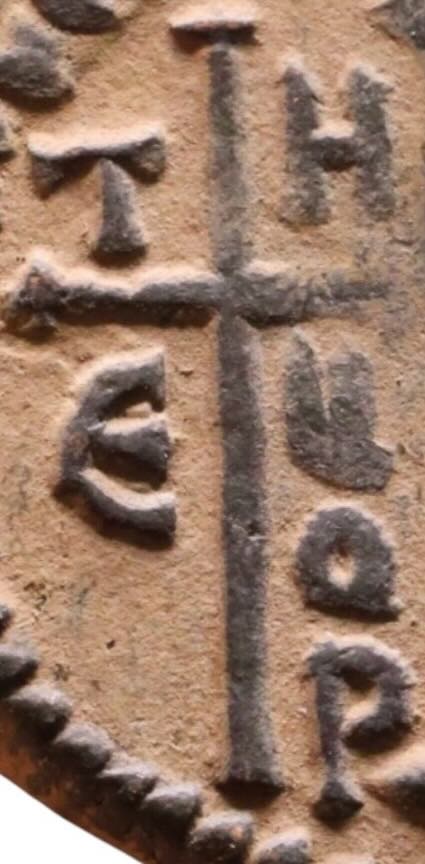

After the name change the half-follis has "TH EU O P" instead of "AN TX" across the cross.

Here is another pre-reform type of the 40-nummus denomination. A new (and unique to Antioch) "enthroned facing" emperor retains a Latin minkmark.

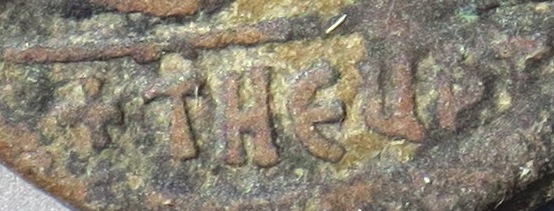

+THEUP

Sear 214

Follis. 34-32 mm. 18.04 grams. 6:00

+THEUP

This type with Justinian enthroned facing occurs only

at Antioch/Theopolis

Struck 531/2-536/7 [Hahn]

+THЄUP+

+THЄUP+

Sear 215A.

Sear 215A.

34 mm. 18.00 grams.

Very similar to type Sear 214 above, but with stars on either side of the M.

+THЄUP+ with a small "o" above the P

(The "o" is continued from the previous issue, Sear 216, and omitted from Sear 214 above.)

This variant is rare and may be a mule with the reverse of Sear 216 (above).

This "enthroned facing" type appears also on the 20-nummus (half-follis) denomination with the city name across the cross.

Sear 225

Sear 225

Half-follis. 20 nummi.

26-24 mm. 9.23 grams.

TH

ΕU

O

P

Struck 531/2-536/7 [Hahn]

In Greek (and Antioch was a Greek-speaking city), Theopolis is spelled θEOYΠOΛIS, which is variously abbreviated on coins.

In 536/7 the profile bust returned when the spelling switched to Greek.

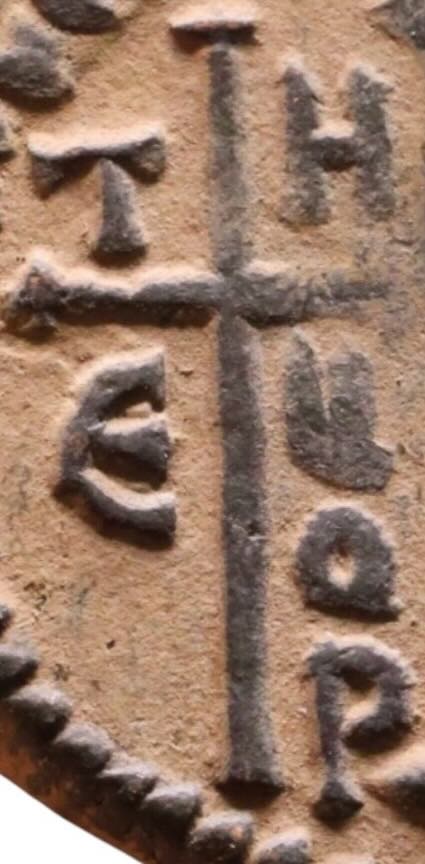

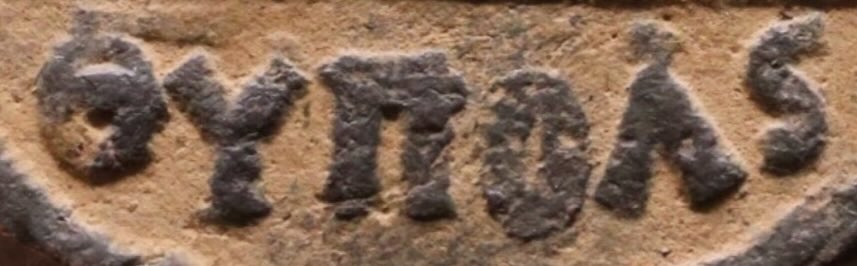

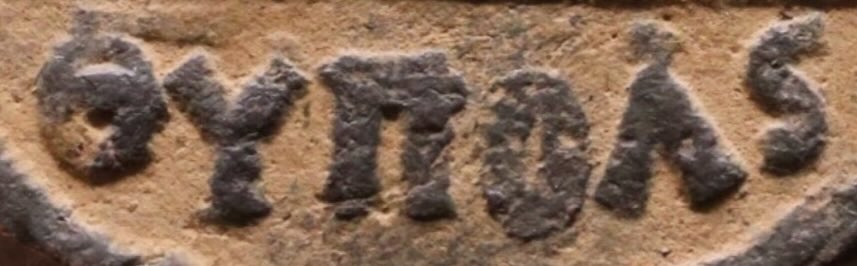

θYΠOΛS (the line over the θY indicates an abbreviation)

Sear 217.

Sear 217.

Follis. 30-28 mm. 14.86 grams.

Bust right.

θYΠOΛS (bar over θY)

This longer version is from before the coinage reform of 538/9 which is distinguished by facing busts.

Struck 536/7- 539 (to be replaced by the frontal bust)

A second example.

A second example.

Sear 217.

Follis. 31-30 mm. 14.50 grams.

The 20-nummi piece has its mintmark in Greek: θYΠOΛS is spelled across the cross, instead of the previous "AN TX" and "TH EU O P" Latin types.

Sear 227

Half-follis. 20 nummi (much of the K is flat).

28-25 mm. 7.86 grams.

With a bar above:

θY (line above)

ΠO

ΛS.

[The vertical stroke of the cross might serve as the "I" of "polis"]

Struck 536/7-539.

The Facing-Bust Coin Reform. The copper coins were reformed in year 12 (538/9) to be larger and have facing busts instead of profile busts. Year 12 (538/9) was the first year with facing portraits at Constantinople, Nicomedia, and Cyzicus. Year 13 was the first year at Antioch and Carthage. At Antioch the new city name, "Theopolis" is abbreviated or spelled out in Greek (Antioch was primarily a Greek-speaking city) on the first folles. After this reform the coins were explicitly dated by regnal year.

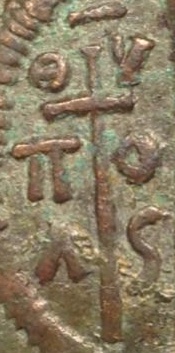

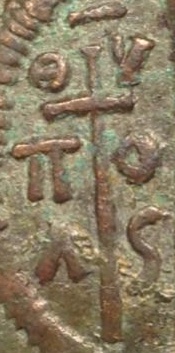

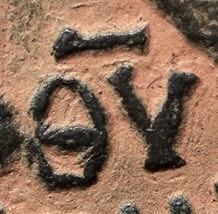

[Only year 13.] "θVΠO" is close to spelling out Theoupolis, with a bar above the "θV" indicating an abbreviation.

[Only year 13.] "θVΠO" is close to spelling out Theoupolis, with a bar above the "θV" indicating an abbreviation.

Sear 218B.

Follis. 39 mm, 20.77 grams.

Mintmark: θVΠO, bar above the "θV",

on a large follis of year 13.

The reform which yielded this new, larger, coin started in year 12 at Constantinople but did not begin at Antioch until year 13 and no coins of Antioch were issued in years 14 or 15 (probably due to the invasion of Khusru mentioned above). The mintmark switched to Latin in year 16 (see the next coin). (There were no coins at Antioch in years 17, 18, or 19 either). So, this short-version mintmark was used only in year 13 making this a one-year type.

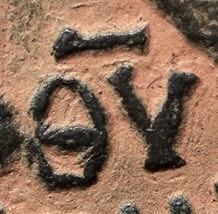

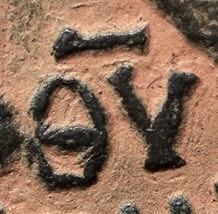

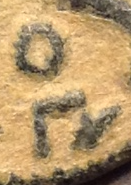

The reformed half-follis (539/540) had the city-name abbreviated even more.

θV with a bar above

Sear 228

Sear 228

Half-follis. 20-nummi

Year 13 (539/40)

33-30 mm. 11.43 grams

θV with a bar above

This short abbreviation was used only on

this denomination and only this year.

The above 20-nummi type and the following 40-nummi type, both of year 13, 539/40, were not issued in years 14 and 15 because of the interruption of the invasion of Khusru I mentioned above. They were also not issued in years 17, 18, or 19, but the reason for the second interruption is not certain [Grierson, Byzantine Coins, page 66]; Hahn suggests it may have been the plague [p. 62].

Year 16 (542/3) was different

CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

Sear 219

Sear 219

Follis.

39-37 mm. 22.53 grams. 6:00.

Year XG = 16 = 542/3.

Mintmark: CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

Hahn 144a.

DO I 216

This mintmark is only from year 16 and no coins with years 17, 18 or 19 were minted, for reasons uncertain, but possibly because of the plague.

CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

Sear 219.

Sear 219.

40 nummi.

38-37 mm. 16.81 grams. 6:00.

Year XG = 16 = 542/3.

Mintmark: CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

Hahn 144a.

DO I 216

The metal of this piece is unusual and granular. The explanation for the fabric is not certain. It could be either an ancient or modern imitation. Another possibility, which I believe, is that the tribulations of the mint forced them to use an irregular metal source. The narrow "X" in the date is also seen on the DO and Hahn specimens from officina Gamma. On this issue the M is wide (leaving less room for the date) and the diagonal strokes of the M do not go to the top of the vertical strokes.

The half-follis from year 16 (542/3) has a mintmark unique to that year--CH with a bar above it.

Sear 229

Sear 229

20 nummi

33 mm. 11.63 grams.

Year XG = 16 = 542/3.

Mintmark: CH, bar over the CH.

Hahn 153

DOC 236

Some authors have drawn the shape of this mintmark as if it had a horizontal at the top, like a T:  (Byzantine Coinage in the East, volume 1). Later there is a mintmark for Theopolis which begins with a T-shape much like that (Sear 221). However, that shape is not on any of these Sear 229 half-follis coins. I think that line-drawing shape is wishful thinking invented to explain the otherwise hard-to-explain "C". (By the way, the "H" may well be our "H", but is also the shape of eta in Greek. So, when we are trying to figure out that mintmark, bear that possibility in mind. Maybe that "C" symbol in the mintmark is playing more than the role of just "T"; maybe plays the role of our "TH" so the mark is our "THE" for Theopolis."

(Byzantine Coinage in the East, volume 1). Later there is a mintmark for Theopolis which begins with a T-shape much like that (Sear 221). However, that shape is not on any of these Sear 229 half-follis coins. I think that line-drawing shape is wishful thinking invented to explain the otherwise hard-to-explain "C". (By the way, the "H" may well be our "H", but is also the shape of eta in Greek. So, when we are trying to figure out that mintmark, bear that possibility in mind. Maybe that "C" symbol in the mintmark is playing more than the role of just "T"; maybe plays the role of our "TH" so the mark is our "THE" for Theopolis."

Minting Resumes in Year 20 (546/7) with a new Mintmark.

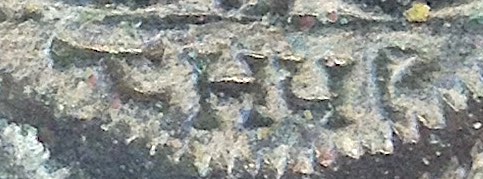

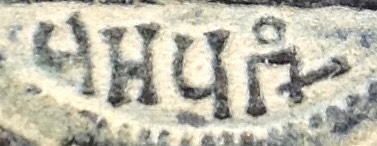

ɥHɥΠo/

Sear 220

Sear 220

Follis.

36-34 mm. 20.03 grams.

Year X/X

Mintmark: ɥHɥΠo/ (o above, / through right side)

DOC I 217c

Officina Γ

Hahn MIBE 145a, year 20

The first symbol of the mintmark does not seem to be any known letter. The H and U are clear. The terminal Π with a slash through its right side and tiny o above is an abbreviation for "polis" which is used later in a stand-alone form. The "H" could be the Greek eta (E). If the first letter were theta (which it does not look like), this would abbreviate "Theoupolis". The slash is like our apostrophe denoting omission of letters [as, for example, in "don't"]

Sear 220.

Sear 220.

Follis.

36-33 mm. 19.70 grams.

Year X/X/I

DO I 218

Hahn 145a year 21.

As above, but year 21.

That mintmark appears on decanummi too.

Sear 236, year 20

Sear 236, year 20

Decanummium. 10 nummi.

23-21 mm.

The first letter is a bit like a U but the stroke on the right continues downward and must have been a local version of T.

The mintmark continues HUΠ with a slash through the right and a tiny o above. The Πo with a slash abbreviates "polis".

Here is another similar mintmark, but for year 21.

Sear 236, year 21

Decanummium. 10 nummi.

22 mm. 4.92 grams.

Type and mintmark are very similar, but with a bar and not a tiny "o" above the pi.

That odd first "letter" is not an error; it appears on all issues of the M and I denominations dated from years 20 to 24. For the K denomination, see further below.

Years 24-38 have the first symbol more like a T.

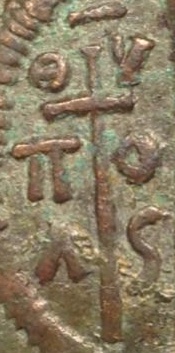

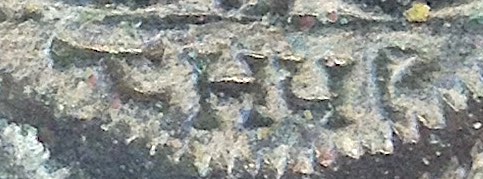

THUΠ/ [T with the stem curved and a terminal Π/ (slash indicates abbreviation). Used years 24-29]

Sear 221.

Sear 221.

Follis. 35-34 mm. 18.73 grams.

Year X/X/G = 26 = 552/3.

Officina Δ

Mintmark THUΠ/ was used years 24-29. It begins in Latin [TH] and ends in Greek [Π]!

In year 30 the mintmark changed to end with rho (P)

Years 28 (554/5) and 30-34 the final symbol can be P or P*.

THUP (T with the stem curved)

Sear 222

Follis.

35 mm. 19.1 grams.

Mintmark THUP

Year X/X/XI = 31 = 557/8

THUP* [T with the stem curved. Used years 28 and 30-34.]

THUP* [T with the stem curved. Used years 28 and 30-34.]

Sear 222 variety (officina E is unlisted for this year)

Follis.

39-34 mm. Remarkably large flan. 17.84 grams. 6:00.

Mintmark: THUP*

Year XXXIII = 33 = 559/560

This mintmark (sometimes without the terminal *) has been found from years 28 and 30-34.

The flan is far larger than the beading, making the coin unusually large for this late date. The DOC examples for this year are only 34mm and 32 mm.

Justinian issued reformed (facing bust) folles in years 12 through 39 (538/9 - 565). Constantinople only minted folles until year 37, Nicomedia through year 34, Cyzicus year 31, Antioch year 39 (the latest), and Carthage year 14. Here is one from Antioch, year 38. Year 39 coins from the final year of Justinian are rare.

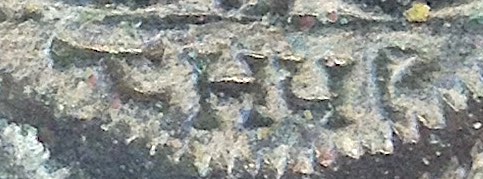

From year 35 an E is inserted into the mintmark and obverse legends become badly blundered. One interest of coins dated years 36-39 at Antioch is their badly blundered obverse legends. The legend had been clear with "IVSTINIANVS" legible and then, in years 36-39, almost none of the lettering was correct.

Sear 223

Sear 223

40 nummi.

34-33 mm. 18.31 grams. 4:30.

Year 35 = 561/2.

Mintmark THЄЧP

Officina Γ

Unlike the following coins, much of the obverse legend is legible, although the lettering is poorly executed.

DN IVSTIN-IANVS PΓ AV

which is all correct except at the end which is usually "PF AVG".

Something happened in year 35 that affected the mint. Crude lettering of the correct legend is replaced by nonsense lettering, as on the next three coins.

Sear 223

Sear 223

40 nummi.

36-31 mm. 15.44 grams. 4:30.

Year 37. XXXGI = 563/4

Mintmark THЄЧP (with no apostrophe)

Officina Γ

The interest of this coin is in the obverse legend.

It used to be correctly spelled:

DN IVSTINIANVS PP AVG

or something very similar. Now, look closely at this coin's obverse legend:

..NPΛSLI-NVPΛLLMΛ. Almost none of the lettering is right. Sear notes, "From regnal year 35 [561/2] the legend is usually badly blundered."

Compare to the next one from the next year with obverse legend

VTNCΛLLM - ΛNPLSP.

Sear 223

Sear 223

40 nummi.

36-34 mm. 19.58 grams. 5:00.

Year 38 = 564/5 -- very late.

Mintmark THЄЧP' (with apostrophe)

Officina Γ

The interest of this coin is in the obverse legend.

It used to be

DN IVSTINIANVS PP AVG or something very similar. Now, look closely at this one and see

VTNCΛLLM - ΛNPLSP

Almost none of the lettering is right. Sear notes, "From regnal year 35 [561/2] the legend is usually badly

This speaks to the sorry state of the mint after all the calamities in Antioch. I am unaware of any historical explanation for why the good obverse legends produced through year 33 (above) began to be blundered in year 35.

Next is another year 38 with a different blundered obverse legend.

THЄUP

Sear 223.

Sear 223.

37-34 mm. 19.49 grams.

Year 38: XXXGII

The obverse legend is something like

..VLDLS - VLLMPSLV

which is very far from correct and pretty far from the other blundered legend above. The bust is not poorly engraved and the reverse lettering is okay. Do we infer that obverse legends were, at Antioch in this late part of Justinian's reign, cut by different engravers than the designs?

Do we think this engraver was illiterate and no one above him in the mint cared if the legend was right?

If the point of minting was to give a stamp of approval to an amount of copper, this is full-size and full weight. Is that all that mattered?

Here are the four obverse legends next to each other:

DN IVSTIN-IANVS PP AVG (year 35)

..NPΛSLI-NVPΛLLMΛ (year 37)

VTNCΛLLM - ΛNPLSP (year 38)

..VLDLS - VLLMPSLV (another year 38)

The late legends have letter shapes, but not words. The mint was in bad shape!

We see blundered legends on the other denomiantions, too.

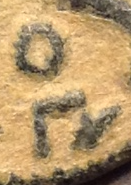

Some half-folles (years 20-29) just indicated the "polis" part of "Theopolis" which apparently was deemed sufficient.

Sear 230

Sear 230

Half-follis. 20 nummi. Year 21 (547/8)

27 mm. 9.41 grams. 10:30.

Mintmark: Π with a slash and o above, for "polis."

The slash is like our apostrophe denoting omission of letters

(as, for example, in "don't")

This mintmark was used only on this denomination and only years 20-29.

The obverse is struck with a decanummium-sized die, too small for the flan, in contrast with the next example where the obverse die is too large for the flan.

Sear 230

Sear 230

Half-follis. 20 nummi.

27-25 mm.

Year 21

Π with a slash and o above.

A rho-like symbol was another abbreviation for "polis" (years 30-34).

Sear 231

Sear 231

20-nummi

Year 30 (556/7)

27-26 mm. 9.69 grams.

A rho-like symbol

for a mintmark

[This is an abbreviation for "polis" in Latin

the way the previous abbreviation is in Greek.]

This mintmark was used only on

this denomination and only years 30-34.

Here is one more type of Justinian from Antioch, this one with a monogram:

Sear 245

Sear 245

5-nummi

16-15 mm. 2.30 grams. 12:00.

Epsilon (for "5") with the middle stroke expanded to a monogram of "IVSTINIANVS"

Some have expanded the monogram to read "ANTIOXIA" for Antioch.

The ANTO and C are evident, and the I possible, but if it is for "Antioch" what is that "V" at the top?

If you have ideas, please let me know:

Sear 245, a second example.

15 mm. 1.39 grams. 12:00

Note that the obverse legend has letter shapes, but does not make his name or any sense. This type is therefore dated late in his reign, say, year 35 = 561 or later, when the dated folles also have garbled obverse legends (Sear 223).

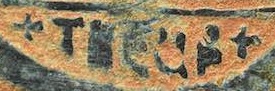

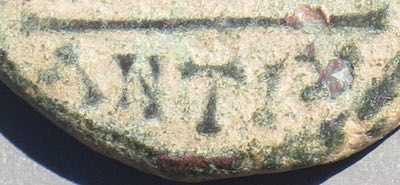

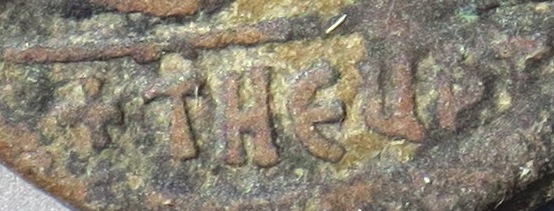

Justin II, 565-578. Justinian was succeded by Justin II. Coins of "year 1" of Justin II are well-produced at other mints, but not at Antioch. The garbled letter forms continue.

Justin II, year 1, 565/6.

Justin II, year 1, 565/6.

35-32 mm. 18.92 grams. Repatinated.

Bust facing with emperor holding Victory on globe, which is a rare depiction and only at Antioch and only from years 1 and 2.

Mintmark: THEUP as on the last coins of Justinian.

Year I with * above and below, to right of the M.

Sear 378.

Note the lettering of the obverse legend.

ΔNIUSTYEI - PPAVC [S, T, Y, E, and C look cut twice or are backwards]

It has lots of shapes which are close to letters, but not quite right.

The problems with the quality of the coins from Antioch had not cleared up for years 1 and 2. Coins of years 3 and 4 were not issued at Antioch (although they were at other mints). The Antioch mint continued to have problems. Coins in the name of Justin II resume for year 5 and show the much more common type with both Justin II and Sophia.

The mintmarks. (Listed twice: by text alone and with an image.)

Mintmarks: ANTIX, ANTX, +THEUP+, θYΠOΛS, θVΠO, θV, CHEUPo, CH, ɥHɥΠo/, THUΠ/, THUP, THUP*, THEUP, P.

Mintmarks arranged vertically:

AN , T H , θY , o

TX E U ΠO Π/

o ΛS

P

Click on an image to go to its coin.

ANTIX  [Illustrated above. Year 1. The rest follow in the text below. ]

[Illustrated above. Year 1. The rest follow in the text below. ]

ANTX

A N/T X in two lines

+THЄUP

+THEUP+ (Small o above the P)  [c. 533-537, years 7-11.]

[c. 533-537, years 7-11.]

θYΠOΛS  [The Greek version of Theopolis. Bar over the ΘΥ, as with the following variants. c. 537-539, years 11-12.]

[The Greek version of Theopolis. Bar over the ΘΥ, as with the following variants. c. 537-539, years 11-12.]

T H/ E U/ O / P in four lines  [c. 529-531, years 3-6, pre-reform]

[c. 529-531, years 3-6, pre-reform]

θ Y/Π O/Λ S in three lines  [The Greek version of Theopolis. Years 9-12, pre-reform.]

[The Greek version of Theopolis. Years 9-12, pre-reform.]

The mintmark changed when Justinian's coin reform introduced the facing bust in year 13 at Antioch (The reform began in year 12 at Constantinople).

θVΠO  [Only year 13, 539/540.]

[Only year 13, 539/540.]

θV  θV bar over the θV [Only year 13, 539/540.]

θV bar over the θV [Only year 13, 539/540.]

CHEUPo  bar over the CH. [Only year 16. (Coins were not minted in years 14, 15, 17, 18, and 19)]

bar over the CH. [Only year 16. (Coins were not minted in years 14, 15, 17, 18, and 19)]

THUΠ/  [Years 24-29]

[Years 24-29]

THUP  and THUP*

and THUP*  [Years 30-34.]

[Years 30-34.]

THEUP  [Years 35-38]

[Years 35-38]

THEUP'  [Years 35-38]

[Years 35-38]

Π with a slash through it and o above  and

and

ρ (a rho-like symbol)  [only on the "K" denomination]

[only on the "K" denomination]

The End (except for references below).

References: Not in alphabetical order, rather order of importance.

Sear, Byzantine Coins and Their Values, second edition, 1987, pages 70-75. [This is an excellent convenient list of types. It has little commentary.]

Grierson, Byzantine Coins, 1982, especially pages 65-67. [This is the most useful reference about mintmarks on coins of Antioch.]

wikipedia under "526 Antioch earthquake" [A good source.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/526_Antioch_earthquake

wikipedia under "Volcanic winter of 536" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volcanic_winter_of_536

Hahn, W. Coins of the Incipient Byzantine Empire. [MIBE] volume 1. [A very well-illustrated complete list of types from Anastasius through Justinian.]

Bellinger, Alfred R. Catalog of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks and Whittemore Collection, volume 1, 1966, pages 133-156 and plates XXXV-XL. [This has coin descriptions and photos, but little useful commentary except on page 141 it lists the mintmarks on denominations and their dates.]

Bellinger, Alfred R. "Byzantine Notes" ANSMN XII (1966) pp. 83-127, especially note 4, pp. 93-96 "The Antiochene Copper of Justinian" (not illustrated). [This article must be read with the corrections from Bates' well-illustrated article in ANSMN 16 (1970). Among other things, the letter form at the begining of the mintmark of classes B, D, E, and F is shown by Bates to be incorrectly written by Bellinger.]

Bates, George E. "Five Byzantine Notes," ANSMN 16 (1970), pp. 69-75 and plates XVI-XXI, especially pp. 60-79 on "A Supplement to 'The Antiochene Copper of Justinian." [The plates illustrate numerous coins from Bates' extensive collection that bear on the mintmarks at Antioch and their dates. Published after DOC volume I came out, it corrects erroneous readings in DOC.]

Procopius, on the result of the Persian sack of Antioch in June 640:

"Everything was everywhere reduced to ashes and leveled to the ground, and since many mounds of ruins was all that was left standing of the burned city, it became impossible for the people of Antioch to recognize the site of each person's house... And since there were no longer public stoas or colonnaded courts in existence anywhere, nor any marketplace remaining, and since the side streets no longer marked off the thoroughfares of the city, they did not any longer dare to build any house." Procopius [d. c. 565] On Buildings.

Drápelová, Pavla. "Province in Contrast to City: Irregularities and Peculiarities in the Coinage of Antioch (518-565)," Chapter 11 in From Constantinople to the Frontier: The City and the Cities, edited by Matheou, N., T. Kampianaki, and L. Bondioli, 2016.

d'Andrea, Alberto, Andrea Ginnasi, and Domenico Moretti. Byzantine Coinage in the East, volume 1. 2019 .

Note 1: Cassius Dio wrote about an earthquke at Antioch in December 115 when emperor Trajan was present, "While the emperor was tarrying in Antioch a terrible earthquake occurred; many cities suffered injury, but Antioch was the most unfortunate of all. Since Trajan was passing the winter there and many soldiers and many civilians had flocked thither from all sides in connection with law-suits, embassies, business or sightseeing, there was no nation or people that went unscathed; and thus in Antioch the whole world under Roman sway suffered disaster." --Cassius Dio Roman History, 24.1. Scholars think it may have been a 7.5 on the Richter scale.

Return to the top of this page.

Go to the main Table of Contents page on Ancient Greek and Roman Coins.

Most Byzantine mint cities had a single clear mintmark, such as "CON" for Constantinople. However, Antioch had more than a dozen very different mintmarks under Justinian. (An illustrated list of the mintmarks is far below.) The city had two distinct names. After catastrophic earthquakes of AD 526 and 528 it changed its name to Theopolis ("City of God"). The earthquakes of February 2023 were similar. (I added Antioch to this map from the New York Times of the Feb. 2023 earthquake.) The tragic history of Antioch is below.

Most Byzantine mint cities had a single clear mintmark, such as "CON" for Constantinople. However, Antioch had more than a dozen very different mintmarks under Justinian. (An illustrated list of the mintmarks is far below.) The city had two distinct names. After catastrophic earthquakes of AD 526 and 528 it changed its name to Theopolis ("City of God"). The earthquakes of February 2023 were similar. (I added Antioch to this map from the New York Times of the Feb. 2023 earthquake.) The tragic history of Antioch is below.  ANTIX

ANTIX

Sear 233

Sear 233

Sear 224A variety. (He notes only officina A and gamma, but this one is B.)

Sear 224A variety. (He notes only officina A and gamma, but this one is B.)

Sear 224A

Sear 224A

ANTIX

ANTIX

+THEUP (no small "o" and the terminal "+" omitted)

+THEUP (no small "o" and the terminal "+" omitted)

Another Sear 216, this one is an imitation.

Another Sear 216, this one is an imitation.

Sear 226

Sear 226

Sear 226, a second example, larger.

Sear 226, a second example, larger.

+THЄUP+

+THЄUP+ Sear 215A.

Sear 215A.

Sear 225

Sear 225

Sear 217.

Sear 217.

[Only year 13.] "θVΠO" is close to spelling out Theoupolis, with a bar above the "θV" indicating an abbreviation.

[Only year 13.] "θVΠO" is close to spelling out Theoupolis, with a bar above the "θV" indicating an abbreviation.

CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

CHEUPo, bar over the CH.

(Byzantine Coinage in the East, volume 1). Later there is a mintmark for Theopolis which begins with a T-shape much like that (

(Byzantine Coinage in the East, volume 1). Later there is a mintmark for Theopolis which begins with a T-shape much like that (

Sear 220

Sear 220

Sear 236, year 20

Sear 236, year 20

Sear 223

Sear 223

Sear 223

Sear 223

Sear 223

Sear 223 THЄUP

THЄUP

Sear 239

Sear 239

Sear 230

Sear 230

Sear 230

Sear 230

Sear 231

Sear 231 Sear 245

Sear 245

Justin II, year 1, 565/6.

Justin II, year 1, 565/6.