Samanid coins. Multiple dirhams.

Samanid coins. Multiple dirhams.

How big are multiple dirhams? A US quarter is 24 mm and seems a good-sized coin, but the large multiple dirhams are much larger at 45 mm. Take a look; it is huge! (It is discussed more below.)

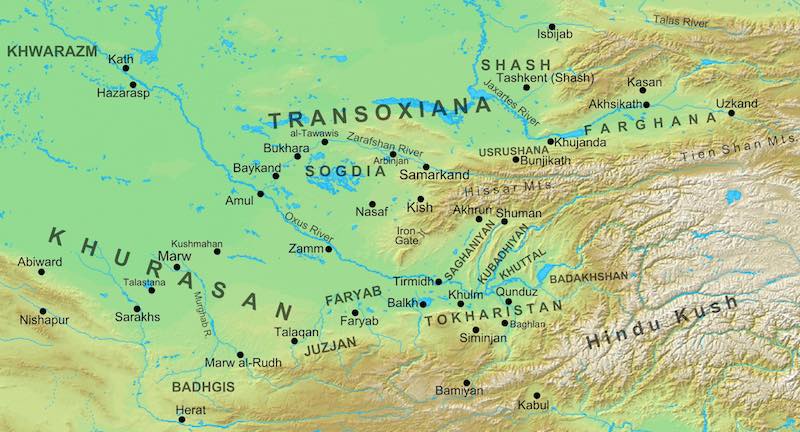

It is almost hard to believe, but at one time Central Asia was very prosperous, with some of the largest and wealthiest cities in the world. "If it is said that a paradise is to be seen in this world, then the paradise of this world is Samarkand." -- 'Ata-Malik Juvaini (Boyle translation.) The fabled cities of Samarkand, Bukhara, Tahskent, and Balkh were on the "Silk Road." (Map by Cplakidas from wikipedia. Get your bearings on the map by locating Kabul and Herat in Afghanistan near the bottom of the map. Samarkand is close to the middle.) However, in 1220 Ghengis Khan swept through and utterly destroyed most of the cities. It is not quite right to say he "conquered" the cities, rather he removed them and their populations from the face of the earth, putting an abrupt end to a bright civilization. The region has not recovered to this day.

The Sunni Samanid dynasty ruled the region called "Transoxiana" and additional territory including Tajikistan and parts of Iran, c. 864 to 1005. They had many very productive silver mines and the large volume of silver produced required mints to convert it into a useful form--coins.

Unlike many Islamic coins, they are not beautifully struck. They minted "multiple dirhams" of two or more times the weight of the dirhem without attempting to make dies larger than the dies for dirhams. They give the distinct impression of just trying to mark the silver as good bullion and sell it.

The Sunni Samanid dynasty ruled the region called "Transoxiana" and additional territory including Tajikistan and parts of Iran, c. 864 to 1005. They had many very productive silver mines and the large volume of silver produced required mints to convert it into a useful form--coins.

Unlike many Islamic coins, they are not beautifully struck. They minted "multiple dirhams" of two or more times the weight of the dirhem without attempting to make dies larger than the dies for dirhams. They give the distinct impression of just trying to mark the silver as good bullion and sell it.

Here is an image of both sides of the first coin:

45 mm. 11.49 grams.

45 mm. 11.49 grams.

Note: Many coins with much smaller diameter weigh more than this. 27 mm tetradrachms of Alexander the Great weigh c. 17 grams. This coin is thinner than Greek and Roman coins (but not paper thin).

3:00 die axis (like Sasanian coins)

Struck in the name of Nuh II, 943-954 (AH 331-342). (The ruler named "Nuh" with these dates used to be called Nuh I.)

Album 1455. "Believed to have been struck posthumously, after c. 367" [Album 4th edition, page 210.]

Steve Album says this variety is unpublished with obverse as SNAT-246 but with Allah.

Sylloge Numorum Araboricum Tübinghen, Balkh und die Landschaften am oberen Oxus, XIVc, by Florian Schwarz).

This example is particularly well-centered and the edges of the dies are clear. The force of the strike was spread out over a broad 45 mm disk making relatively few pounds per square centimeter resulting in, almost always, weak strikes. This strike, even with its weakness, is better than most. This piece was probably minted at Balkh.

This example is particularly well-centered and the edges of the dies are clear. The force of the strike was spread out over a broad 45 mm disk making relatively few pounds per square centimeter resulting in, almost always, weak strikes. This strike, even with its weakness, is better than most. This piece was probably minted at Balkh.

Balkh, the most common mint, is at the red marker on the google map, in what is now northern Afghanistan. Samarkand and Bukhara are in Uzbekistan north of Balkh. There were productive silver mines in the upper Zarafshan River valley (near Samarkand, in the middle of the map, in modern Uzbekistan). To be able to mint silver coins requires a source of silver. Conversely, having a source of silver practically requires minting silver coins. The silver is valuable; what else can you do with it?

Silk road trade sent very many dirhams (of c. 3 grams of silver each) to Vikings lands. Remarkably, about a hundred thousand Samanid dirhams have been discovered in large hoards in Scandanavia and Russia![1] Also, very large "multiple dirhams" were minted. Their weights are irregular, centering around 11-12 grams (the weight of 4 dirhams), but with some were significantly lighter and some significantly heavier. There are many Samanid coins broader and heavier than dirhams that don't seem to be any particular multiple of the dirham. Therefore scholars have argued these large coins were effectively a way to move bullion and must have been weighed for each transaction. They apparently only traveled within the Samanid empire and are rarely found elsewhere. They were rare until the 1970s when a large hoard was discovered. Now they are common, especially when compared to the number of collectors who want them.

Here is another piece, not so large, to the same scale:

33 mm. (A US half-dollar is less than 31 mm.) 4.96 grams. (Which is not a clear multiple of the dirhams which were about 2.97 grams.)

33 mm. (A US half-dollar is less than 31 mm.) 4.96 grams. (Which is not a clear multiple of the dirhams which were about 2.97 grams.)

Attributed to ibn Mansur, 976-997 (AH 366-387)

and struck at Balkh.

Mitchiner, World of Islam, 710, page 139.

Again, the typical weak strike is evident.

The most accessible source for identification of Samanid coins is The World of Islam by Michael Mitchner (1977), pages 132-149, with 59 examples of this large diameter illustrated and identified (The coins are difficult to decipher and attributions, especially to mints, are often uncertain. Not all scholars agree with Mitchiner's readings). The coinage was so vast that far from all of the types are illustrated. The coin above is similar to Mitchiner 728, but not the same. Mitchner also wrote the hard-to-find book, The Multiple Dirhems of Medieval Afghanistan (1973) which has 169 pages and discusses over 800 pieces classified into more than 120 types. (The book was reviewed by Steve Album in NC 1976.) More up to date is a book by Florian Schwarz, Sylloge Numorum Arabicorum Tübingen: Balkh und die Landschaften am oberen Oxus, Tubingen, Volume 14c. 2002, which is described as "180 pages, 77 plates, softcover. 1500+ coins listed. The volume describes and illustrates on 181 pages and 79 b/w plates 1,526 Islamic coins minted in what corresponds to modern northern Afghanistan and Tadjikistan; about half of the coins were minted in Balkh, the other mints are Andaraba, Badakhshan, Tashqurghan, Tirmidh, Hisar, Khuttal, Rasht, Saghaniyan, Tayiqan, Kishm, Wakhsh, Walwalij / Qunduz, and al-Yun/Khust ("lands on the Upper Oxus", as the German title translates). It contains sections on multiple dirhams (ca. 170)."

Digital images can be enlarged to any size, making it hard to grasp just how large a 45 mm coin really is (Silver dollars are only 38.1 mm.) Perhaps the comparison with a US quarter helps, but holding one in the hand is far more impressive.

It hard for westerners to think that cities in this region were once among the most beautiful, advanced, and glorious in the world.

Notes:

1) Islamic Coin Hoards and the Trade Routes: How Dirhams Reached the North by Dr. Aram Vardanyan. He notes, by country, hoards totaling over 100,000 coins. Also, "The Vikings brought their goods southwards by Volga and exchanged or sold them to oriental merchants. From the narrative sources one can conclude that the Vikings brought to the South slaves, furs, honey, leather, ivory, fish and other goods. On their way back the Vikings took with them to the North both goods and Islamic coins, mainly in silver, and then buried the coins in their lands for further purposes. The coins were accumulated in such big numbers, that the Vikings buried them as hoards. Today, the number of hoards of Islamic silver coins revealed in Scandinavia and Baltic Sea area, as well as in Eastern Europe exceeds several hundreds." "The proportion of Samanid coins in the hoards can demonstrate how intensively was the trade between the Vikings and Middle Asia between 900 and 960 AD."

"in the Viking period there were at least three main routes that provided an inflow of Islamic dirham to the North. One was taking from the Middle Asia, the important cities of Mawarannahr, such as Samarkand, Bukhara, al-Shash. ... Another important trade route was going from Iraq, through Mesopotamia and Armenia to Darband and then through the northern Caucasus up to Volga. ... the third important way how Islamic coins could become a part of hoards buried in the North was connecting the merchants of Mesopotamia, Syria and Levant with the Rus and Vikings lay through the Byzantine Empire."

Roman K. Kovalev considered 1620 dirham hoards (hoards with 5 or more dirhams) from western Eurasia [European Russia and Baltic lands] of which 281 had dirhams stuck in tenth century Bukhara, in "Mint output in Tenth Century Bukhara: A Case Study of Dirham Production and Monetary Circulation in Northern Europe," Russian History/Histoire Russe 28 (2001) pp. 245-271. Bukhara was the capital of the Samanid empire. He states, "The overwhelming majority of dirhams stuck in Bukhara were exported to northern Europe." [p. 265]

Thomas Noonan and Roman Kovalev consider 302 hoards with coins from Balkh in "The dirham output and monetary circulation of a secondary Samanid mint: A case study of Balkh."

Go to the Table of Contents of this entire educational site.

Samanid coins. Multiple dirhams.

Samanid coins. Multiple dirhams. Samanid coins. Multiple dirhams.

Samanid coins. Multiple dirhams. 45 mm. 11.49 grams.

45 mm. 11.49 grams.  This example is particularly well-centered and the edges of the dies are clear. The force of the strike was spread out over a broad 45 mm disk making relatively few pounds per square centimeter resulting in, almost always, weak strikes. This strike, even with its weakness, is better than most. This piece was probably minted at Balkh.

This example is particularly well-centered and the edges of the dies are clear. The force of the strike was spread out over a broad 45 mm disk making relatively few pounds per square centimeter resulting in, almost always, weak strikes. This strike, even with its weakness, is better than most. This piece was probably minted at Balkh. 33 mm. (A US half-dollar is less than 31 mm.) 4.96 grams. (Which is not a clear multiple of the dirhams which were about 2.97 grams.)

33 mm. (A US half-dollar is less than 31 mm.) 4.96 grams. (Which is not a clear multiple of the dirhams which were about 2.97 grams.)